While the chance of debris hitting an aircraft is very low, the research highlights that the potential for uncontrolled space rocket junk to disrupt flights and create additional costs for airlines and passengers is not.

Space junk disrupting air traffic is far from unheard of. In 2022, a re-entering 20-tonne piece of rocket prompted Spanish and French aviation authorities to close parts of their airspace.

And with rocket launches and flights increasing, University of British Columbia researchers say policymakers need to take action.

“The recent explosion of a SpaceX Starship shortly after launch demonstrated the challenges of having to suddenly close airspace,” said first author Ewan Wright, an interdisciplinary studies doctoral student at UBC. “The authorities set up a ‘keep out’ zone for aircraft, many of which had to turn around or divert their flight path. And this was a situation where we had good information about where the rocket debris was likely to come down, which is not the case for uncontrolled debris re-entering the atmosphere from orbit.”

When objects such as satellites are launched by rockets into space, large portions of the rockets are often left in orbit. If these leftover rocket stages have a low enough orbit, they can re-enter the atmosphere in an uncontrolled way. Most of the material will burn up in the atmosphere, but many pieces still hurtle towards the ground.

Rocket launches, flights increasing #

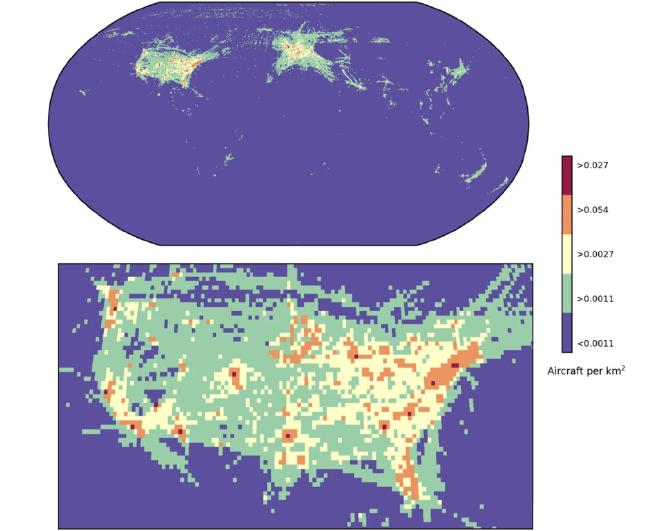

The researchers used the number of aircraft on the busiest day of 2023 and matched it to the probability of rocket pieces re-entering above various levels of air traffic, calculated using a decade of data. Denver, Colorado had the highest density of air traffic on that day, at about one aircraft every 18km2.

Using this as their peak, they calculated the probability of rocket junk re-entering the atmosphere over different air traffic density thresholds. When they looked at regions that have 10 per cent of the peak air traffic density or higher, for instance—the type of activity seen in the airspace over Vancouver-Seattle—they found a 26 per cent chance per year of rocket junk re-entering in that type of airspace.

“Notably, the airspace over southern Europe that was closed in 2022 is only five per cent of the peak. Around the world, there is a 75-per-cent chance of a re-entry in such regions each year,” said Wright.

There were 258 successful rocket launches in 2024, and a record 120 uncontrolled rocket debris re-entries, with more than 2,300 rocket bodies still in orbit. Air passenger numbers are expected to increase by almost seven per cent in 2025, according to the International Air Transport Association.

Space industry exporting risk #

The researchers also calculated the annual probability of space rocket junk colliding with an aircraft at one in 430,000.

When space rocket junk enters into busy air space, aviation authorities either roll the dice and allow flights to continue or act by diverting flights or closing airspace. “But why should authorities have to make these decisions in the first place? Uncontrolled rocket body re-entries are a design choice, not a necessity,” said co-author Dr. Aaron Boley, associate professor in the department of physics and astronomy. “The space industry is effectively exporting its risk to airlines and passengers.”

Rather, the industry could use rockets that are designed to re-enter the atmosphere in a controlled way after use, crashing harmlessly into the ocean. This solution requires collective international action, said co-author Dr. Michael Byers, a UBC political science professor. “Countries and companies that launch satellites won’t spend the money to improve their rockets designs unless all of them are required to do so,” said Dr. Byers. “So, we need governments to come together and adopt some new standards here.”

The paper by Wright et al., as the researches states in the SR paper builds on a preliminary study presented by the authors at the 2nd International Orbital Debris Conference: Uncontrolled reentries will disrupt airspace again. While there is overlap in the text, the new article greatly expands upon that initial work.

“On 4 November 2022, a 20 tonne Long March 5B (LM-5B) rocket body reentered the atmosphere over the Pacific Ocean. This reentry location was a result of chance rather than design, as the rocket body was abandoned in orbit and left to return to Earth in an uncontrollable manner. In the evening before its reentry, the rocket body was predicted to reenter over southern Europe. This led the European Union Space Surveillance and Tracking organisation (EU SST) to raise concerns with the European Aviation Safety Agency (EASA), which in response issued a Safety Information Bulletin (SIB) recommending that national authorities ‘consider implementing and notifying airspace restrictions on a path of minimum 70 km and up to 120 km on each side of the estimated re-entry trajectory’. The following morning, Spanish and French authorities elected to do just that, and closed part of their airspace”.

“Of the 15 notices to air missions (NOTAMs) issued across Europe for the reentry, four were zero-rated, meaning the airspace was effectively closed. These closures delayed 645 aircraft by an average of 29 min, and covered central Spain, southern France, and Monaco. Particularly disruptive were the short lead times between the announcement of a closure and its implementation—in some cases, aircraft already in flight had to be diverted or instructed to return to their departure airport. Surrounding states, including Portugal, Italy and Greece, were also under the reentry flight path and subject to the same reentry risk, but elected not to close their airspace. They then saw an unexpected increase in air traffic from diverted flights, which carried different, operational risks. The incident highlighted, among other things, a lack of preparation for this eventuality and a lack of harmonization of responses among states”, as you can read on SR site.

-

The paper Airspace closures due to reentering space objects was published in Scientific Reports. Authors: Ewan Wright, Aaron Boley & Michael Byers.

-

The article One in four chance per year that rocket junk will enter busy airspace, written by Alex Walls, was published in the news section of the University of British Columbia.