Señales mixtas: cómo interpreta el cerebro las señales sociales; autismo y disfunciones neurológicas

Table of Contents

“Cuando experimentamos el mundo e interactuamos con la gente, utilizamos todos nuestros sentidos”, dice el profesor de Cold Spring Harbor Laboratory, Stephen Shea. “Eso es cierto para los animales y los humanos”. Sin embargo, ese no siempre es el caso en trastornos del desarrollo como el autismo. Estas afecciones pueden afectar la forma en que el cerebro procesa la información entrante, lo que dificulta la interpretación de las señales sociales que impulsan las conversaciones, las citas y otras actividades interpersonales.

No se entiende bien exactamente cómo se mezclan y se influyen entre sí estas señales en el cerebro. _Para arrojar luz sobre el tema, Shea y la estudiante de posgrado Alexandra Nowlan rastrearon cómo interactúan el olfato y la audición en los cerebros de ratones durante un comportamiento maternal llamado rescate de crías. Esta actividad no se limita a las madres. También la pueden aprender las madres sustitutas. Pensemos en madrastras, niñeras.

¿Por qué tener en brazos a una cría produce tanta alegría? Para los ratones, cuidar de sus crías es una recompensa en sí misma. El vídeo muestra en tiempo real cómo el cerebro impulsa los instintos maternales. ¿Ves el medidor parecido a un electrocardiograma que recorre la pantalla? Cada pico es una inyección de dopamina liberada por el cerebro en el momento exacto en que una madre ratón toma a una cría.

El profesor asociado del Laboratorio Cold Spring Harbor, Stephen Shea, y el posdoctorado Yunyao Xie rastrearon esta respuesta neurológica hasta un proceso llamado aprendizaje por refuerzo. Cada dosis de dopamina crea la expectativa de futuras recompensas, lo que impulsa a las madres ratón a volver a tomar a sus crías.

Comprender cómo funciona esto en ratones ofrece a los investigadores una pista sobre cómo nuestro propio cerebro fomenta las interacciones sociales. También podría enseñarnos algo sobre el autismo y otros trastornos del desarrollo neurológico.

Si tienes interés en este tema, puedes ver The Science of Supermoms

Amígdala basal y corteza auditiva #

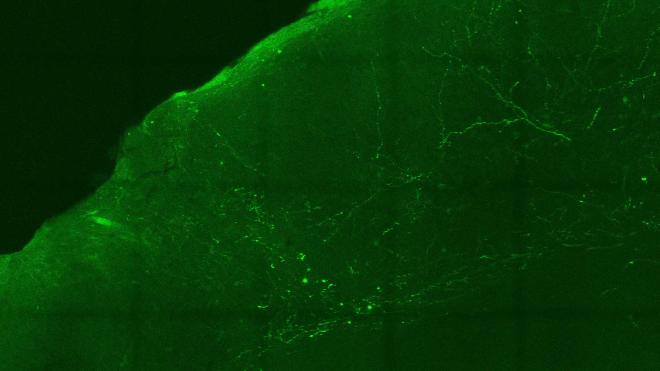

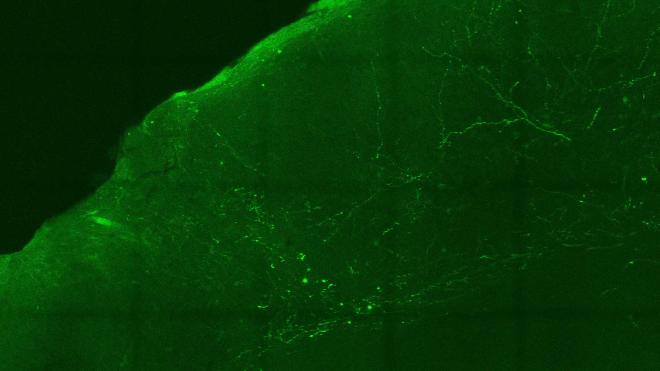

“Hallar y cobijar a las crías es una de las cosas más importantes para las madres o los cuidadores. Requiere la capacidad de olerlas y oírlas. Si ambas cosas son importantes, eso puede significar que se fusionan en algún lugar del cerebro. Una cosa interesante que encontramos fue una proyección desde un lugar llamado amígdala basal (AB)”, explicó Shea.

En ratones y humanos, la AB está involucrada en el aprendizaje y procesamiento de señales sociales y emocionales. Durante la recuperación de las crías, el equipo descubrió que las neuronas de la AB llevan señales olfativas al centro auditivo del cerebro, la corteza auditiva (CA). Allí, se fusionan con las señales sonoras entrantes e influyen en la respuesta del animal a futuros sonidos, como los llantos de las crías. Sorprendentemente, cuando el equipo de Shea impidió que los ratones madres accedieran a las señales olfativas, su respuesta de recuperación de las crías se descompuso casi por completo.

“Creemos que lo que llega a la corteza auditiva se filtra a través de señales socioemocionales de las neuronas del cerebro asexual”, explicó Shea. “Ese procesamiento puede verse afectado en el autismo y en las enfermedades neurodegenerativas. Creemos que muchas partes del cerebro participan en este comportamiento y que está muy bien controlado”.

El equipo de Shea ahora está explorando cómo estas regiones cerebrales se conectan e interactúan entre sí. Su trabajo puede llevar a una mejor comprensión de cómo el autismo puede afectar la capacidad de una persona para interpretar las señales sociales. Pero eso es sólo el comienzo.

“La idea de que hayamos encontrado un circuito neuronal que permita que los procesos emocionales interactúen directamente con la percepción me resulta muy emocionante”, afirmó Shea. Y no es el único que piensa así. Su investigación podría aportar respuestas a una de las preguntas más antiguas de la humanidad: ¿cómo influyen nuestros sentidos en la forma en que nos conectamos con los demás y experimentamos el mundo?

Importante #

-

La investigación fue financiada por el National Institute of Mental Health, y la C.M. Robertson Foundation.

-

El paper Multisensory integration of social signals by a pathway from the basal amygdala to the auditory cortex in maternal mice fue publicado en Current Biology. Autores: Alexandra C. Nowlan ∙ Jane Choe ∙ Hoda Tromblee ∙ Clancy Kelahan ∙ Karin Hellevik & Stephen D. Shea

-

El artículo Mixed signals: How the brain interprets social cues, con la firma de Nick Wurm, Communications Specialist fue publicado en la sección de noticias de CSHL

-

Citation

Nowlan, A.C., et al., “Multisensory integration of social signals by a pathway from the basal amygdala to the auditory cortex in maternal mice”, Current Biology, December 3, 2024. DOI: 10.1016/j.cub.2024.10.078

- Instalaciones núcleo: “El centro de recursos compartidos para animales alberga y cuida a los animales esenciales para la investigación científica. Nuestro personal se encarga de todos los aspectos de la cría de animales, garantiza una atención humanitaria y ayuda a los investigadores con procedimientos altamente técnicos y diseño y desarrollo de protocolos”. — Directora de instalaciones para animales y veterinaria asistente Rachel Rubino, DVM

English version #

Mixed signals: How the brain interprets social cues #

Imagine you’re at a dinner party, but you can’t smell the food cooking or hear the dinner bell. Sounds like a dream, right? What if it wasn’t?

“When we experience the world and interact with people, we use all our senses,” Cold Spring Harbor Laboratory Professor Stephen Shea says. “That’s true for animals and humans.” However, that’s not always the case in developmental disorders like autism. These conditions can affect how the brain processes incoming information, making it difficult to interpret the social cues that drive conversations, dates, and other interpersonal activities.

Exactly how such signals mix and influence each other in the brain isn’t well understood. __To shed light on the subject, Shea and graduate student Alexandra Nowlan traced how smell and hearing interact in mouse brains during a maternal behavior called pup retrieval_. This activity isn’t limited to mothers. It can also be learned by surrogates. Think stepmoms and babysitters.

Pup retrieval #

Why does holding a baby bring so much joy? For mice, tending to their young is its own reward. This video shows in real time how the brain drives maternal instincts. See the EKG-like meter running across the screen? Each spike is a shot of dopamine released by the brain at the exact moment a mother mouse picks up a pup.

Cold Spring Harbor Laboratory Associate Professor Stephen Shea and Postdoc Yunyao Xie traced this neurological response to a process called reinforcement learning. Each shot of dopamine creates the expectation of future rewards, driving mouse moms to pick up their pups again.

Understanding how this works in mice gives researchers a clue about how our own brains encourage social interactions. It could also teach us something about autism and other neurodevelopmental disorders.

May be you want to read…? The Science of Supermoms

Basal amygdala and auditory cortex #

“Pup retrieval is one of the most important things for mothers or caregivers. It requires the ability to smell and hear the pup. If these things are both important, that may mean they merge somewhere in the brain. One interesting thing we found was a projection from a location called the basal amygdala (BA)," explains Shea.

In mice and humans, the BA is involved in learning and processing social and emotional signals. During pup retrieval, the team found that BA neurons carry smell signals to the brain’s hearing center, the auditory cortex (AC). There, they merge with incoming sound signals and influence the animal’s response to future sounds—like pups’ cries. Amazingly, when Shea’s team blocked maternal mice from accessing smell signals, their pup retrieval response almost completely broke down.

“We think what’s reaching the AC is being filtered through social-emotional signals from BA neurons,” Shea explains. “That processing can be impaired in autism and neurodegenerative conditions. We think many parts of the brain participate in this behavior and that it’s very richly controlled.”

Shea’s lab is now exploring how these brain regions connect and interact with one another. Their work may lead to a better understanding of how autism can affect a person’s ability to interpret social cues. But that’s just the beginning.

“The idea that we found a neural circuit that may allow emotional processes to directly interact with perception is very exciting to me,” Shea says. He’s not alone there. His research might yet provide answers to one of humanity’s oldest questions. How do our senses inform the ways we connect with one another and experience the world?

Important #

-

The study was supported by National Institute of Mental Health, and C.M. Robertson Foundation

-

The paper Multisensory integration of social signals by a pathway from the basal amygdala to the auditory cortex in maternal mice was published in Current Biology. Authors: Alexandra C. Nowlan ∙ Jane Choe ∙ Hoda Tromblee ∙ Clancy Kelahan ∙ Karin Hellevik & Stephen D. Shea

-

Citation

Nowlan, A.C., et al., “Multisensory integration of social signals by a pathway from the basal amygdala to the auditory cortex in maternal mice”, Current Biology, December 3, 2024. DOI: 10.1016/j.cub.2024.10.078

-

Core Facilites Animal Facility “The Animal Shared Resource houses and cares for the animals essential for scientific research. Our staff perform all aspects of animal husbandry, ensure humane care, and assist researchers with highly technical procedures and protocol design and development.” — Animal Facility Director and Attending Veterinarian Rachel Rubino, DVM

-

The article Mixed signals: How the brain interprets social cues, signed by Nick Wurm Communications Specialist, was published in CSHL news’s section