¿Una infección intestinal tiene un papel sorprendente en la enfermedad de Alzheimer?

Table of Contents

Investigadores de la Universidad Estatal de Arizona y del Instituto Banner Alzheimer, junto con sus colaboradores, han descubierto, en un subconjunto de personas, un vínculo sorprendente entre una infección intestinal crónica causada por un virus común y el desarrollo de la enfermedad de Alzheimer .

Se cree que la mayoría de los seres humanos están expuestos a este virus, llamado citomegalovirus o HCMV, durante las primeras décadas de vida. El citomegalovirus es uno de los nueve virus del herpes, pero no se considera una enfermedad de transmisión sexual. El virus suele transmitirse a través de la exposición a fluidos corporales y se propaga solo cuando el virus está activo.

Según la nueva investigación, en algunas personas, el virus puede permanecer activo en el intestino, desde donde puede viajar al cerebro a través del nervio vago, una importante vía de información que conecta el intestino con el cerebro. Una vez allí, el virus puede alterar el sistema inmunitario y contribuir a otros cambios asociados con la enfermedad de Alzheimer.

Si se confirman las hipótesis de los investigadores, podrían evaluar si los medicamentos antivirales existentes podrían tratar o prevenir esta forma de enfermedad de Alzheimer. Actualmente están desarrollando un análisis de sangre para identificar a las personas que tienen una infección activa por HCMV y que podrían beneficiarse de la medicación antiviral.

“Creemos que hemos encontrado un subtipo biológicamente único de Alzheimer que puede afectar entre el 25% y el 45% de las personas con esta enfermedad”, afirmó el Dr. Ben Readhead, coautor principal del estudio y profesor asociado de investigación del Centro de Investigación de Enfermedades Neurodegenerativas ASU-Banner en el Instituto de Biodiseño de la ASU. “Este subtipo de Alzheimer incluye las características placas amiloides y ovillos de tau (anomalías cerebrales microscópicas que se utilizan para el diagnóstico) y presenta un perfil biológico distintivo de virus, anticuerpos y células inmunitarias en el cerebro”.

Los hallazgos fueron publicados hoy en “Alzheimer’s & Dementia: The Journal of the Alzheimer’s Association”. Investigadores de ASU, Banner Alzheimer’s Institute, Banner Sun Health Research Institute y el Translational Genomics Research Institute (TGen) lideraron el esfuerzo colaborativo, que incluyó investigadores de la Facultad de Medicina Chan de UMass, el Instituto de Biología de Sistemas, el Centro Médico de la Universidad Rush, la Facultad de Medicina Icahn en Mount Sinai y otras instituciones.

CD83 #

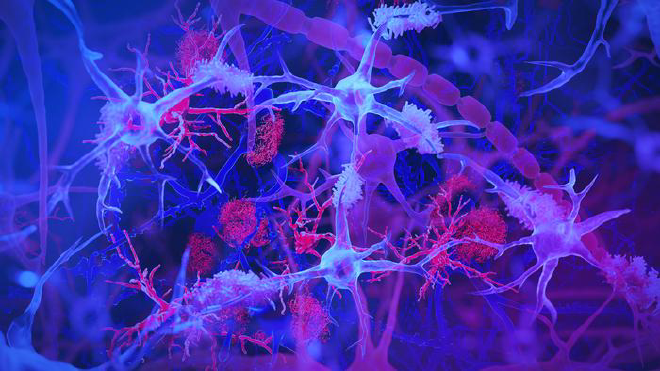

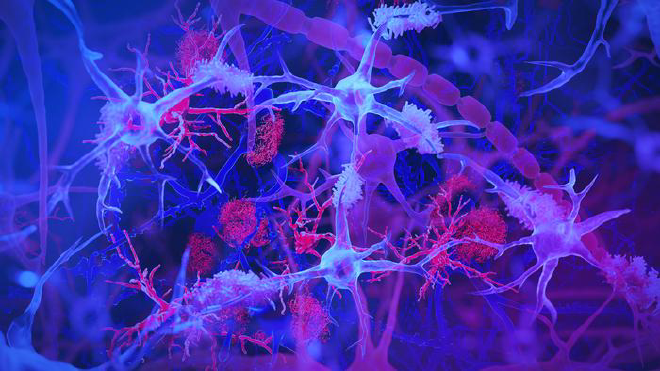

El equipo de investigación sugiere que algunas personas expuestas al HCMV1 desarrollan una infección intestinal crónica. Luego, el virus ingresa al torrente sanguíneo o viaja a través del nervio vago hasta el cerebro. Allí, es reconocido por las células inmunes del cerebro, llamadas microglia, que activan la expresión de un gen específico llamado CD83. El virus puede contribuir a los cambios biológicos involucrados en el desarrollo del Alzheimer.

El papel de las células inmunitarias del cerebro, la microglia, o células inmunitarias del cerebro, se activa cuando se responde a infecciones. Si bien inicialmente tiene un efecto protector, un aumento sostenido de la actividad microglial puede provocar inflamación crónica y daño neuronal, lo que está implicado en la progresión de enfermedades neurodegenerativas, incluido el Alzheimer.

En un estudio publicado a principios de este año en “ Nature Communications”, los investigadores descubrieron que los cerebros post mortem de los participantes de la investigación con enfermedad de Alzheimer tenían más probabilidades que los de los que no la padecían de albergar específicamente microglia CD83(+). Al investigar por qué ocurría esto, descubrieron un anticuerpo en los intestinos de estos sujetos, lo que es coherente con la posibilidad de que una infección pudiera contribuir a esta forma de Alzheimer.

Hepatitis C #

En el estudio más reciente, los investigadores intentaron comprender qué podría impulsar la producción de anticuerpos intestinales. El equipo examinó el líquido cefalorraquídeo de estos mismos individuos, lo que reveló que los anticuerpos estaban específicamente dirigidos contra el virus de la hepatitis C. Esto motivó la búsqueda de pruebas de infección por el virus de la hepatitis C en el intestino y el tejido cerebral de estos sujetos, y así lo encontraron.

También observaron HCMV en el nervio vago de los mismos sujetos, lo que plantea la posibilidad de que así es como el virus viaja al cerebro. En colaboración con la Universidad RUSH, los investigadores pudieron reproducir la asociación entre la infección por citomegalovirus y la microglia CD83(+) en una cohorte independiente de pacientes con Alzheimer.

Para investigar más a fondo el impacto de este virus, el equipo de investigación utilizó modelos de células cerebrales humanas para demostrar la capacidad del virus de inducir cambios moleculares relacionados con esta forma específica de la enfermedad de Alzheimer. La exposición al virus aumentó la producción de proteínas amiloide y tau fosforilada y contribuyó a la degeneración y muerte de las neuronas.

¿HCMV es responsable de la enfermedad de Alzheimer en algunas personas? #

El HCMV puede infectar a personas de todas las edades. En la mayoría de las personas sanas, la infección se produce sin síntomas, pero puede presentarse como una enfermedad leve similar a la gripe. Alrededor del 80% de las personas muestran evidencia de anticuerpos a los 80 años. No obstante, los investigadores detectaron HCMV intestinal sólo en un subconjunto de individuos, y esta infección parece ser un factor relevante en la presencia del virus en el cerebro. Por este motivo, los investigadores señalan que el simple hecho de entrar en contacto con HCMV, que le ocurre a casi todo el mundo, no debería ser motivo de preocupación.

Y, aunque los investigadores propusieron hace más de 100 años que virus o microbios dañinos podrían contribuir a la enfermedad de Alzheimer, ningún patógeno ha sido vinculado consistentemente con la enfermedad.

Los investigadores proponen que estos dos estudios ilustren el impacto potencial que pueden tener las infecciones en la salud cerebral y la neurodegeneración en general. Sin embargo, añaden que se necesitan estudios independientes para poner a prueba sus hallazgos y las hipótesis resultantes.

La NOMIS Foundation, Banner Alzheimer’s Foundation, National Institutes of Health, and Arizona Alzheimer’s Consortium apoyaron el estudio. Los biorepositorios únicos de Arizona, en particular el Brain and Body Donation Program en el Banner Sun Health Research Institute, proporcionaron muestras de tejido y recursos, incluidos el colon, el nervio vago, el cerebro y el líquido cefalorraquídeo. Rush University-led Religious Orders Study y Memory and Aging Study proporcionaron muestras y datos cerebrales adicionales. Esto permitió a los investigadores realizar una investigación más matizada, destacando las raíces sistémicas en lugar de las puramente neurológicas de la enfermedad de Alzheimer.

“Estamos sumamente agradecidos a nuestros participantes, colegas y a quienes nos apoyaron en el trabajo, por la oportunidad de avanzar en esta investigación de una manera que ninguno de nosotros podría haber hecho por nuestra cuenta”, dijo el Dr. Eric Reiman, Director Ejecutivo del Banner Alzheimer’s Institute y autor principal del estudio. “Estamos entusiasmados por la oportunidad de que los investigadores prueben nuestros hallazgos de maneras que marquen una diferencia en el estudio, la subtipificación, el tratamiento y la prevención de la enfermedad de Alzheimer”.

Los hallazgos del estudio reciente plantean una pregunta importante: ¿podrían los medicamentos antivirales ayudar a tratar a los pacientes de Alzheimer que tienen una infección crónica por HCMV?

Los investigadores están trabajando ahora en un análisis de sangre para identificar a las personas con este tipo de infección intestinal crónica por HCMV. Esperan utilizarlo junto con los nuevos análisis de sangre para el Alzheimer para evaluar si los medicamentos antivirales existentes podrían utilizarse para tratar o prevenir esta forma de enfermedad de Alzheimer.

-

Instituciones de investigación involucradas en el estudio, publicado en la revista Alzheimer’s & Dementia: ASU-Banner Neurodegenerative Disease Research Center en el Biodesign Institute de ASU; Weill Cornell Medicine; Icahn School of Medicine; University of Massachusetts Chan Medical School; The Translational Genomics Research Institute; Institute for Systems Biology; Serimmune, Inc; Rush University Medical Center; Banner Sun Health Research Institute y Banner Alzheimer’s Institute.

-

El artículo The surprising role of gut infection in Alzheimer’s disease, firmado por Sandra Leander fue publicado en la sección de noticias de la Arizona State University

English version #

The surprising role of gut infection in Alzheimer’s disease #

Arizona State University and Banner Alzheimer’s Institute researchers, along with their collaborators, have discovered a surprising link between a chronic gut infection caused by a common virus and the development of Alzheimer’s disease in a subset of people.

It is believed most humans are exposed to this virus — called cytomegalovirus or HCMV — during the first few decades of life. Cytomegalovirus is one of nine herpes viruses, but it is not considered a sexually transmitted disease. The virus is usually passed through exposure to bodily fluids and spread only when the virus is active.

According to the new research, in some people, the virus may linger in an active state in the gut, where it may travel to the brain via the vagus nerve — a critical information highway that connects the gut and brain. Once there, the virus can change the immune system and contribute to other changes associated with Alzheimer’s disease.

If the researchers’ hypotheses are confirmed, they may be able to evaluate whether existing antiviral drugs could treat or prevent this form of Alzheimer’s disease. They are currently developing a blood test to identify people who have an active HCMV infection and who might benefit from antiviral medication.

“We think we found a biologically unique subtype of Alzheimer’s that may affect 25% to 45% of people with this disease,” said Dr. Ben Readhead, co-first author of the study and research associate professor with ASU-Banner Neurodegenerative Disease Research Center in the Biodesign Institute at ASU. “This subtype of Alzheimer’s includes the hallmark amyloid plaques and tau tangles—microscopic brain abnormalities used for diagnosis—and features a distinct biological profile of virus, antibodies and immune cells in the brain.”

The findings were published today in “Alzheimer’s & Dementia: The Journal of the Alzheimer’s Association.” Researchers from ASU, Banner Alzheimer’s Institute, Banner Sun Health Research Institute, and the **Translational Genomics Research Institute (TGen) led the collaborative effort, which included investigators from UMass Chan Medical School, Institute for Systems Biology, Rush University Medical Center, Icahn School of Medicine at Mount Sinai, among other institutions.

:The research team suggests that some people exposed to HCMV develop a chronic intestinal infection. The virus then enters the bloodstream or travels through the vagus nerve to the brain. There, it is recognized by the brain’s immune cells, called microglia, which turn on the expression of a specific gene called CD83. The virus may contribute to the biological changes involved in the development of Alzheimer’s_.

The role of the brain’s immune cells #

Microglia, or the brain’s immune cells, are activated when responding to infections. While initially protective, a sustained increase in microglial activity may lead to chronic inflammation and neuronal damage, which is implicated in the progression of neurodegenerative diseases, including Alzheimer’s.

In a study published earlier this year in “ Nature Communications”, the researchers found that the postmortem brains of research participants with Alzheimer’s disease were more likely than those without Alzheimer’s to harbor specifically CD83(+) microglia. While exploring why this occurred, they discovered an antibody in the intestines of these subjects — consistent with the possibility that an infection could contribute to this form of Alzheimer’s.

In the newest study, investigators sought to understand what might be driving the intestinal antibody production. The team examined spinal fluid from these same individuals, which revealed that the antibodies were specifically against HCMV. This prompted a search for evidence of HCMV infection in the intestine and brain tissue of these subjects - which they found.

They also saw HCMV within the vagus nerve of the same subjects, raising the possibility that this is how the virus travels to the brain. Working with RUSH University, the researchers were able to reproduce the association between cytomegalovirus infection and CD83(+) microglia in an independent cohort of Alzheimer’s patients.

To further investigate the impact of this virus, the research team then used human brain cell models to demonstrate the virus’s ability to induce molecular changes related to this specific form of Alzheimer’s disease. Exposure to the virus did increase the production of amyloid and phosphorylated tau proteins and contributed to the degeneration and death of neurons.

Is HCMV to blame for Alzheimer’s disease in some people? #

HCMV can infect humans of all ages. In most healthy individuals, infection occurs without symptoms but may present as a mild, flu-like illness. About 80% of people show evidence of antibodies by age 80. Nonetheless, the researchers detected intestinal HCMV only in a subset of individuals, and this infection seems to be a relevant factor in the presence of the virus in the brain. For this reason, the researchers note that simply coming into contact with HCMV, which happens to almost everyone, should not be cause for concern.

And, although researchers proposed more than 100 years ago that harmful viruses or microbes could contribute to Alzheimer’s disease, no single pathogen has consistently been linked to the disease.

The researchers propose these two studies illustrate the potential impact that infections can have on brain health and neurodegeneration broadly. Yet, they add that independent studies are needed to put their findings and resulting hypotheses to the test.

The NOMIS Foundation, Banner Alzheimer’s Foundation, National Institutes of Health, and Arizona Alzheimer’s Consortium supported the study. Arizona’s unique biorepositories, particularly the Brain and Body Donation Program at Banner Sun Health Research Institute, provided tissue samples and resources, including the colon, vagus nerve, brain and spinal fluid. Rush University-led Religious Orders Study and Memory and Aging Study provided additional brain samples and data. This allowed researchers to conduct a more nuanced investigation, highlighting the systemic rather than purely neurological roots of Alzheimer’s disease.

“We are extremely grateful to our research participants, colleagues, and supporters for the chance to advance this research in a way that none of us could have done on our own,” said Dr. Eric Reiman, Executive Director of Banner Alzheimer’s Institute and the study’s senior author. “We’re excited about the chance to have researchers test our findings in ways that make a difference in the study, subtyping, treatment and prevention of Alzheimer’s disease.”

The findings of the recent study raise an important question: Could antiviral medications help treat Alzheimer’s patients who have a chronic HCMV infection?

The investigators are working now on a blood test to identify individuals with this type of chronic intestinal HCMV infection. They hope to use it in conjunction with emerging Alzheimer’s blood tests to evaluate whether existing antiviral drugs could be used to treat or prevent this form of Alzheimer’s disease.

-

Research institutions involved in the study, published in the journal Alzheimer’s & Dementia: ASU-Banner Neurodegenerative Disease Research Center in the Biodesign Institute at ASU; Weill Cornell Medicine; Icahn School of Medicine; University of Massachusetts Chan Medical School; The Translational Genomics Research Institute; Institute for Systems Biology; Serimmune, Inc; Rush University Medical Center; Banner Sun Health Research Institute; and Banner Alzheimer’s Institute.

-

The surprising role of gut infection in Alzheimer’s disease, signed by Sandra Leander was published on news section from Arizona State University

-

El citomegalovirus (CMV) es un género de herpesvirus dentro de la subfamilia Betaherpesvirinae, de la familia Herpesviridae. Su nombre se debe al aumento de tamaño que se observa en las células infectadas debido al debilitamiento del citoesqueleto. Prevalencia y afectación: El CMV se encuentra en muchas especies de mamíferos y es común infectar a personas de todas las edades. En los Estados Unidos, casi 1 de cada 3 niños ya se ha infectado por el citomegalovirus antes de tener 5 años, y más de la mitad de los adultos han sido infectados antes de cumplir los 40 años. Síntomas y diagnóstico: Los síntomas de una infección por citomegalovirus son poco específicos y pueden incluir dolor muscular, fiebre por arriba de 38°C o ganglios adoloridos. En muchos casos, no existe ningún síntoma, ya que el virus puede permanecer dormido por mucho tiempo. El diagnóstico se realiza con el examen de sangre CMV durante la gestación, lo que puede dar como resultado: IgG positivo: la mujer ya tuvo el contacto con el virus hace tiempo y el riesgo de transmisión es mínimo. IgM positivo y IgG negativo: infección aguda por citomegalovirus, lo que es más preocupante y requiere orientación médica para el tratamiento. IgM y IgG positivos: se debe realizar una prueba de avidez. Complicaciones y riesgos: La infección con CMV puede ser grave o fatal para pacientes con inmunodeficiencia y para fetos durante el embarazo. En pacientes inmunodeprimidos, la infección puede producir complicaciones severas. Sin embargo, en personas con sistema inmunitario saludable, la infección suele ser asintomática. Reactivación y persistencia: El CMV es un tipo de virus del herpes, que permanece en el cuerpo durante toda la vida después de la infección. Si el sistema inmunitario se debilita en el futuro, este virus puede reactivarse y causar síntomas. La mejor forma de confirmar la infección es mediante un diagnóstico médico y no mediante síntomas o pruebas caseras. Fuentes: Wikipedia en español, MedLinePlus, CDC ↩︎