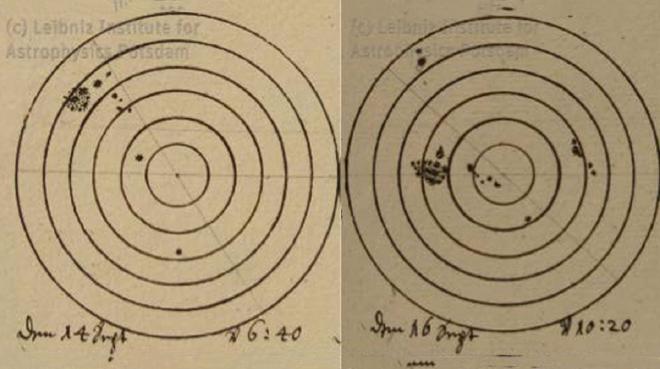

Now science historians -remember Daniella García Almeida in an article on Eos.org -worldwide have come together to compile and digitize 400 years’ worth of sunspot drawings in the hopes of illuminating solar activity of the past and informing our present understanding. Solar physicist Andrés Muñoz-Jaramillo used this digitized collection of sunspot observations to develop a collection of software tools to analyze solar cycles and reconstruct missing gaps.

Learning from the Past #

Solar cycles typically last 11 years, but Muñoz-Jaramillo said that the best instruments for observing the Sun, like the Parker Solar Probe and the Solar Dynamics Observatory, have been around for only about 2 decades. To understand solar variability going back centuries, researchers must look to techniques of the past.

“Whenever we’re dealing with long-term variability, we don’t have the luxury of waiting 100 years to get better data,” said Muñoz-Jaramillo.

Historians have been diligently collecting and digitizing centuries of drawings and creating detailed logs of the position and size of spots over time. Researchers are now using these logs to study the long-term variability of the Sun.

But hundreds of years’ worth of data are difficult to handle. So Muñoz-Jaramillo and his colleagues developed a computational framework to support the efforts of solar cycle researchers worldwide. This collection of software tools uses Bayesian statistics to fill in the gaps where sunspot data may not be available.

“You can make these statements now in a probabilistic way about what went on in these historical periods,” said Muñoz-Jaramillo.

The researchers used this new framework to learn more about the Maunder Minimum, a time period in the 15th century when the Sun was less active and very few sunspots were observed—a few dozen in comparison to the tens of thousands typically observed. With so few data points, any additional information can help scientists better understand the solar activity of the time, Muñoz-Jaramillo said. They also examined another slow activity period in the late 16th century called the Dalton Minimum and compared recent solar activity to that of previous centuries.

Using this framework, they learned that the Maunder and Dalton Minima might have been preceded by other cycles with deep minima in solar activity spread far apart in time. Some heliophysicists speculate that there may be entire solar cycles’ worth of observations missing, Muñoz-Jaramillo said.

Muñoz-Jaramillo and his colleagues presented these results on 16 December at AGU’s Annual Meeting 2025 in New Orleans.

Spotting the Sun’s Evolution #

“This study is highly innovative because, until now, reconstructions of past solar activity have relied solely on sunspot counts,” José Manuel Vaquero Martínez, a physics professor at the Universidad de Extremadura, Spain who was not involved in the study, said in an email. “In contrast, this approach incorporates not only the number of sunspots but also their positions. In other words, it leverages our understanding of how solar active regions (in this case, sunspots) evolve to reconstruct past solar activity.”

Citation #

- The study SH23E-2620 Reconstruction of 400 years of solar activity using probabilistic programming was presented on Agu25 Conference. Authors: Andrés Muñoz-Jaramillo (first author), Southwest Research Institute Boulder & Hisashi Hayakawa, Nagoya University

—Daniella García Almeida, Science Writer

Citation: García Almeida, D. (2025), Sunspot drawings illuminate 400 years of solar activity, Eos, 106, https://doi.org/10.1029/2025EO250477. Published on 17 December 2025. Text © 2025. The authors. CC BY-NC-ND 3.0 Except where otherwise noted, images are subject to copyright. Any reuse without express permission from the copyright owner is prohibited.

Contact [Notaspampeanas](mailto: notaspampeanas@gmail.com)