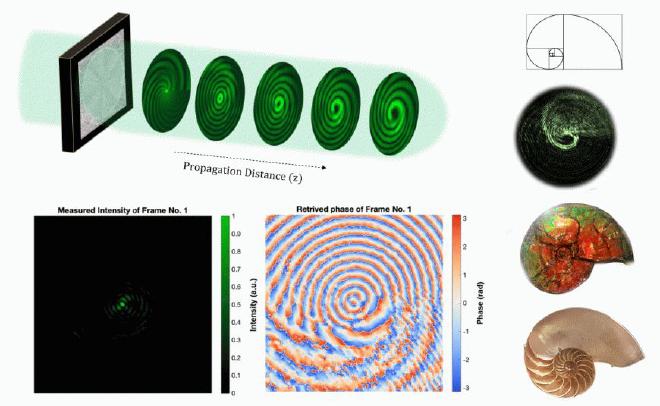

Beams of light that can be guided into corkscrew-like shapes called optical vortices are used today in a range of applications. Pushing the limits of structured light, Harvard applied physicists in the John A. Paulson School of Engineering and Applied Sciences (SEAS) report a new type of optical vortex beam that not only twists as it travels but also changes in different parts at different rates to create unique patterns. The way the light behaves resembles spiral shapes common in nature.

The researchers borrowed from classical mechanics to nickname their never-before-demonstrated light vortex an “optical rotatum,” to describe how the torque on the light’s corkscrew shape gradually changes. In Newtonian physics, “rotatum” is the rate of change in torque on an object over time.

Anne J. Manning wrote that the optical rotatum was created in the lab of Federico Capasso, the Robert L. Wallace Professor of Applied Physics and the Vinton Hayes Senior Research Fellow in Electrical Engineering at SEAS. “This is a new behavior of light consisting of an optical vortex that propagates through space and changes in unusual ways,” Capasso said. “It is potentially useful for manipulating small matter.” The research was published in Science Advances.

In a peculiar twist, the researchers found that their orbital angular momentum-carrying beam of light grows in a mathematically recognizable pattern found all over the natural world. Mirroring the Fibonacci number sequence (made famous in The Da Vinci Code), their optical rotatum propagates in a logarithmic spiral that is seen in the shell of a nautilus, the seeds of a sunflower, and the branches of trees.

“That was one of the unexpected highlights of this research,” said first author Ahmed Dorrah, a former research associate in Capasso’s lab, now an assistant professor at Eindhoven University of Technology. “Hopefully we can inspire others who are specialists in applied mathematics to further study these light patterns and gain unique insights into their universal signature.”

“We show even more versatility of control, and we can do it continuously,” said Alfonso Palmieri, a graduate student in Capasso’s lab and co-author of this research.

While others have demonstrated torque-changing light using high-intensity lasers and bulky setups, the Harvard team made theirs with a single liquid crystal display and a low-intensity beam. By showing they can create a rotatum in an industry-compatible, integrated device, the barrier to entry for their technology to become reality is much lower than previous demonstrations.

Citation #

- The paper Rotatum of light was published in Science Advances

Rotatum of light

Ahmed H. Dorrah , Alfonso Palmieri, Lisa Li, and Federico Capasso Authors Info & Affiliations

Science Advances

11 Apr 2025

Vol 11, Issue 15

DOI: 10.1126/sciadv.adr9092