Los cielos más oscuros y más claros del mundo -en Chile- en peligro por un megaproyecto industrial

Table of Contents

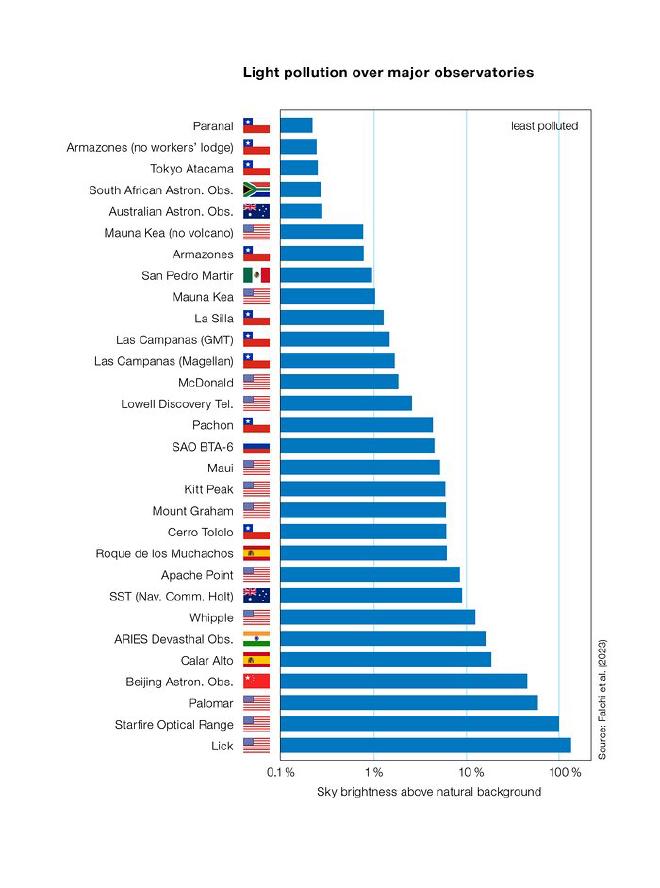

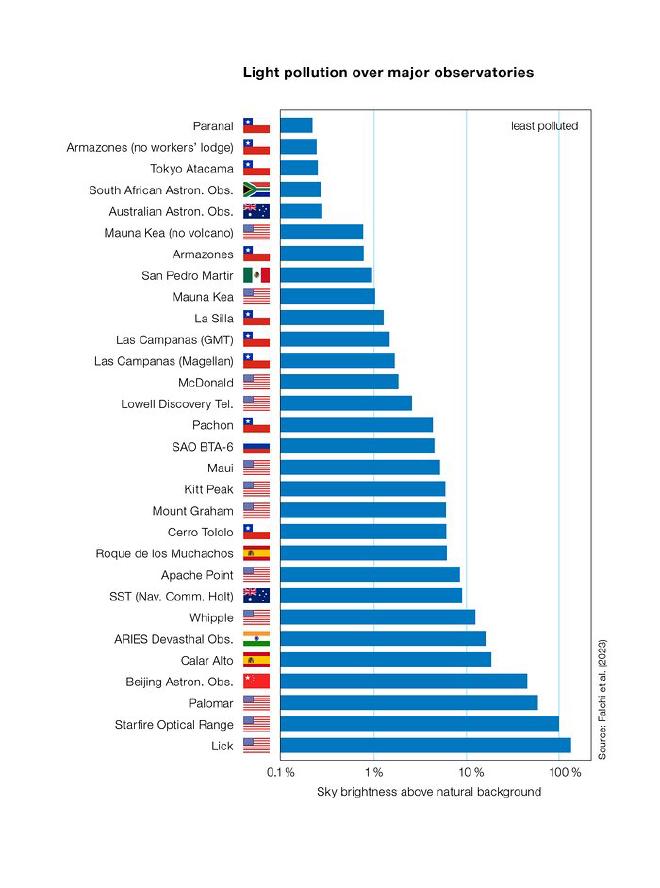

El 24 de diciembre, AES Andes, una subsidiaria de la empresa eléctrica estadounidense AES Corporation, presentó un proyecto para un complejo industrial masivo para evaluación de impacto ambiental, según indicó el European Southern Observatory en un comunicado. Este complejo amenaza los cielos prístinos del Observatorio Paranal del Observatorio Europeo Austral (ESO, por European Southern Observatory) en el desierto de Atacama en el norte de Chile, el más oscuro y claro de todos los observatorios astronómicos del mundo. El megaproyecto industrial está planeado para ubicarse a sólo 5 a 11 kilómetros de los telescopios de Paranal, lo que causaría daños irreparables a las observaciones astronómicas, en particular debido a la contaminación lumínica emitida durante la vida operativa del proyecto. Reubicar el complejo salvaría uno de los últimos cielos oscuros verdaderamente prístinos de la Tierra.

Patrimonio irremplazable para la Humanidad #

Desde su inauguración en 1999, el Observatorio Paranal, construido y operado por el Observatorio Europeo Austral (ESO), ha propiciado importantes avances astronómicos, como la primera imagen de un exoplaneta y la confirmación de la expansión acelerada del Universo. El Premio Nobel de Física de 2020 se otorgó por la investigación sobre el agujero negro supermasivo en el centro de la Vía Láctea, en la que los telescopios de Paranal fueron fundamentales. El observatorio es un activo clave para los astrónomos de todo el mundo, incluidos los de Chile, que ha visto crecer sustancialmente su comunidad astronómica en las últimas décadas. Además, el cercano Cerro Armazones alberga la construcción del Extremely Large Telescope (ELT) de ESO, el telescopio más grande del mundo de su tipo, una instalación revolucionaria que cambiará drásticamente lo que sabemos sobre nuestro Universo.

“La proximidad del megaproyecto industrial AES Andes a Paranal supone un riesgo crítico para los cielos nocturnos más prístinos del planeta”, aseguró el Director General de ESO, Xavier Barcons. “Las emisiones de polvo durante la construcción, el aumento de la turbulencia atmosférica y, especialmente, la contaminación lumínica afectarán de manera irreparable las capacidades de observación astronómica, que hasta ahora han atraído inversiones multimillonarias por parte de los gobiernos de los Estados miembros de ESO”.

El impacto sin precedentes del megaproyecto de AES Andes #

El proyecto abarca un complejo industrial de más de 3000 hectáreas, lo que se acerca al tamaño de una ciudad o distrito, como Valparaíso, Chile o Garching cerca de Múnich, Alemania. Incluye la construcción de un puerto, plantas de producción de amoniaco e hidrógeno y miles de unidades de generación eléctrica cerca de Paranal.

La belleza del cielo nocturno se revela sobre el Cerro Paranal, sede del Very Large Telescope (VLT). Las Nubes de Magallanes, Pequeña y Grande, se pueden ver hacia el horizonte mientras los meteoritos atraviesan el cielo. Todo capturado en este time-lapse durante la Expedición de Ultra Alta Definición de ESO. Crédito: ESO/B. Tafreshi

Gracias a su estabilidad atmosférica y a la ausencia de contaminación lumínica, el desierto de Atacama es un laboratorio natural único para la investigación astronómica. Estos atributos son esenciales para proyectos científicos que buscan abordar cuestiones fundamentales, como el origen y la evolución del Universo o la búsqueda de vida y la habitabilidad de otros planetas.

Un llamado a proteger los cielos chilenos #

“Chile, y en particular Paranal, es un lugar verdaderamente especial para la astronomía: sus cielos oscuros son un patrimonio natural que trasciende sus fronteras y beneficia a toda la humanidad”, afirmó Itziar de Gregorio, representante de ESO en Chile. “Es crucial considerar ubicaciones alternativas para este megaproyecto que no pongan en peligro uno de los tesoros astronómicos más importantes del mundo”. La reubicación de AES Andes es la única forma efectiva de prevenir daños irreversibles a los cielos únicos de Paranal. Esta medida no sólo salvaguardará el futuro de la astronomía, sino que también preservará uno de los últimos cielos oscuros verdaderamente prístinos de la Tierra.

English version #

World’s darkest and clearest skies at risk from industrial megaproject #

On December 24th, AES Andes, a subsidiary of the US power company AES Corporation, submitted a project for a massive industrial complex for environmental impact assessment. This complex threatens the pristine skies above ESO’s Paranal Observatory in Chile’s Atacama Desert, the darkest and clearest of any astronomical observatory in the world. The industrial megaproject is planned to be located just 5 to 11 kilometres from telescopes at Paranal, which would cause irreparable damage to astronomical observations, in particular due to light pollution emitted throughout the project’s operational life. Relocating the complex would save one of Earth’s last truly pristine dark skies.

An irreplaceable heritage for humanity #

Since its inauguration in 1999, Paranal Observatory, built and operated by the European Southern Observatory (ESO), has led to significant astronomy breakthroughs, such as the first image of an exoplanet and confirming the accelerated expansion of the Universe. The Nobel Prize in Physics in 2020 was awarded for research on the supermassive black hole at the centre of the Milky Way, in which Paranal telescopes were instrumental. The observatory is a key asset for astronomers worldwide, including those in Chile, which has seen its astronomical community grow substantially in the last decades. Additionally, the nearby Cerro Armazones hosts the construction of ESO’s Extremely Large Telescope (ELT), the world’s biggest telescope of its kind — a revolutionary facility that will dramatically change what we know about our Universe.

“The proximity of the AES Andes industrial megaproject to Paranal poses a critical risk to the most pristine night skies on the planet,” highlighted ESO Director General, Xavier Barcons. “Dust emissions during construction, increased atmospheric turbulence, and especially light pollution will irreparably impact the capabilities for astronomical observation, which have thus far attracted multi-billion-Euro investments by the governments of the ESO Member States."

The unprecedented impact of a megaproject #

_The project encompasses an industrial complex of more than 3000 hectares, which is close to the size of a city, or district, such as Valparaiso, Chile or Garching near Munich, Germany. It includes constructing a port, ammonia and hydrogen production plants and thousands of electricity generation units near Paranal.

Thanks to its atmospheric stability and lack of light pollution, the Atacama Desert is a unique natural laboratory for astronomical research. These attributes are essential for scientific projects that aim to address fundamental questions, such as the origin and evolution of the Universe or the quest for life and the habitability of other planets.

The call to protect the Chilean skies #

“Chile, and in particular Paranal, is a truly special place for astronomy — its dark skies are a natural heritage that transcends its borders and benefits all humanity,” said Itziar de Gregorio, ESO’s Representative in Chile. “It is crucial to consider alternative locations for this megaproject that do not endanger one of the world’s most important astronomical treasures.”

The relocation of this project remains the only effective way to prevent irreversible damage to Paranal’s unique skies. This measure will not only safeguard the future of astronomy but also preserve one of the last truly pristine dark skies on Earth.