Los cimientos de las viviendas se están desmoronando. Y ¿la pirrotina tiene la culpa?

Table of Contents

Benjamin Cassidy escribió en EOS un artículo que parece una película de terror, de las buenas, porque lo señalado es terrible, o de clase C, porque aún no hay respuestas para los afectados.

Karen Bilotti y su esposo, Sam, comenzaron a notar líneas finas en las paredes de concreto de su sótano, señaló Cassidy. Normalmente, es posible que no lo hubieran pensado dos veces. Pero los Bilotti habían oído hablar recientemente de un grupo cada vez mayor de propietarios de viviendas cercanas, en Massachusetts con grietas más grandes en sus cimientos, y Sam empezó a preocuparse.

“‘Con nuestra suerte, nuestra casa probablemente se vea afectada’”, recordó Karen que le dijo. “Y yo dije: ‘Estás loco’. Eres absolutamente ridículo. No hay manera’”.

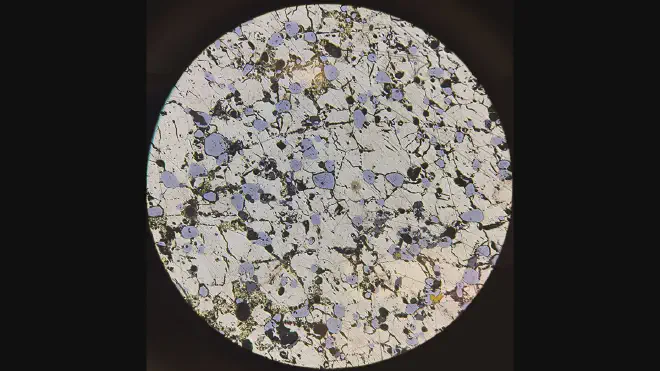

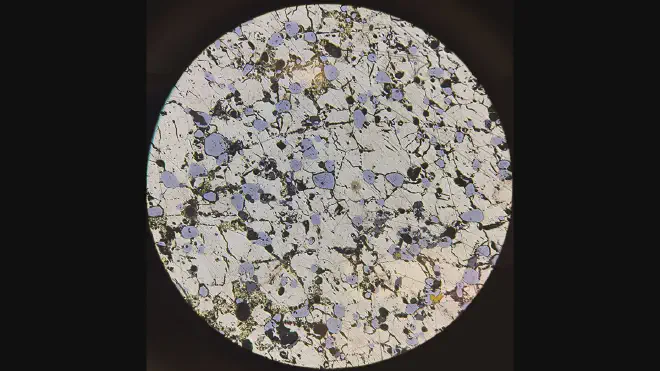

A través de pruebas de núcleos, científicos e ingenieros habían determinado que el culpable de fisuras como las de las casas de sus vecinos era la pirrotita, un mineral compuesto de azufre y hierro que se encuentra en algunos agregados de concreto. Cuando se expone al aire y al agua, la pirrotita puede descomponerse en minerales secundarios que causan la fractura de los cimientos, la erosión de la integridad estructural y el deterioro del valor de la vivienda.

“Es como si a tu casa le hubieran diagnosticado cáncer”, dijo Michelle Loglisci, fundadora de Massachusetts Residents Against Crumbling Foundations, una organización de base de propietarios que luchan por legislación y ayuda financiera en el estado en que residen.

No era la primera vez que los Bilotti se enfrentaban a una catástrofe inmobiliaria. En 2011, un tornado arrasó el oeste y el centro de Massachusetts, arrancando de los cimientos la estructura de su casa anterior como si fuera una casa de muñecas retorcida.

Los Bilotti no querían reconstruir. Así que compraron una casa en otra parte de la ciudad, “la casa de nuestros sueños”, dijo Bilotti, pensando que habían dejado atrás su mala fortuna. Y ahora la casa de sus sueños enfrentaba un futuro incierto.

Efectivamente, una prueba reveló que eran positivos para pirrotita. Al igual que muchos otros propietarios de viviendas en Massachusetts, se enfrentaron a una decisión desalentadora: vivir sabiendo que los cimientos de su casa estaban fallando gradualmente o pagar hasta 300.000 dólares para reemplazarlos sin ninguna garantía de apoyo futuro por parte del estado.

Durante años, los funcionarios públicos de Estados Unidos asociaron esta pesadilla inmobiliaria con Connecticut, donde los investigadores atribuyeron el agregado contaminado con pirrotita de una cantera a hasta 35.000 cimientos defectuosos en el estado. Pero los informes cada vez más extensos sobre cimientos afectados en Massachusetts han aumentado la preocupación entre los científicos y los defensores de los propietarios de viviendas de que el concreto defectuoso es un problema más extendido (uno con poca supervisión actual o histórica) de lo que se pen|saba anteriormente. Recientemente, un complejo de condominios con cimientos agrietados en Dracut, Massachusetts, justo al sur de la frontera con New Hampshire, dio positivo por pirrotita. Más allá de Nueva Inglaterra, la pirrotita de dos canteras conocidas en Canadá dañó miles de hogares desde la década de 1990, y los estudios realizados en los últimos dos años revelaron sus efectos de deterioro incluso en Irlanda.

Los descubrimientos en estas regiones han apuntalado un área incipiente de investigación científica. En mayo pasado, la primera Conferencia Internacional sobre Reacciones de Sulfuro de Hierro en Concreto incluyó presentaciones sobre pruebas de pirrotita, comprensión de su reactividad y mapeo del mineral.

La convocatoria a la pre conferencia. Y los resultados tras el encuentro. La conferencia también reveló una cantera en Massachusetts que había dado positivo en pirrotita. Algunos investigadores piensan que puede haber más: “Tiene que haber otras canteras”, dijo Kay Wille, investigadora principal del equipo de la University of Connecticut’s Crumbling Concrete Research and Testing.

Sin pruebas generalizadas y obligatorias para detectar pirrotita, los científicos no pueden determinar el alcance del hormigón defectuoso ni cómo contener su propagación. “Puede suceder en todas partes si no existe una regulación que garantice que no suceda”, dijo Pierre-Luc Fecteau, investigador de la Universidad Laval que ayudó a organizar la conferencia en Canadá.

Para superar las estrictas barreras regulatorias, los proveedores de concreto generalmente “prueban todo”, dijo Craig Dauphinais, director ejecutivo de la Asociación de Productores de Concreto y Agregados de Massachusetts, un grupo comercial que representa a la industria del concreto en Massachusetts y Rhode Island. Pero Connecticut no exigió que las canteras informaran el contenido de azufre y, en algunos casos, pirrotita hasta 2022, y Massachusetts sólo aprobó en 2023 una ley que exige que las canteras realicen pruebas de compuestos de azufre, aunque las pruebas aún no han comenzado, dijo John Goggin, experto en comunicaciones, analista del Departamento de Transporte de Massachusetts. Hasta que Connecticut rastreó sus cimientos agrietados hasta un proveedor de concreto en su estado, la pirrotita no estaba en el radar de la industria, según Dauphinais.

“Nadie sabía sobre este mineral”, dijo. “Nadie sabía que había un problema relacionado con el concreto premezclado”.

La pirrotita es fácil de pasar por alto. El mineral de bronce sigue siendo menos frecuente que la pirita, un sulfuro de hierro conocido como oro de los tontos. Pero al igual que sus parientes de aspecto lucrativo, este mineral poco común se ha hecho conocido por su engaño: mezclarse con el hormigón resistente y, muy gradualmente, desmoronarlo.

La pirrotita por sí sola no provoca este deterioro. Cuando el sulfuro de hierro altamente reactivo encuentra agua y oxígeno, se transforma en minerales de sulfato (ettringita, taumasita y yeso) que ocupan más espacio que la pirrotita que están reemplazando. Esta expansión de volumen presiona la mezcla circundante de agregado, cemento y agua en el concreto, obligándolo a agrietarse. Este fenómeno se llama ataque interno de sulfato.

“Es como un proceso muy difícil, desafiante de frenar, detener o prevenir”, dijo Wille.

Durante mucho tiempo, el ataque ocurre bajo la superficie y las grietas pueden tardar entre 10 y 30 años en aparecer. Pero una vez que comienza el astillamiento, explicó Wille, la degradación del hormigón se acelera, ya que las fisuras exponen la pirrotita a más humedad y oxígeno.

Atrincherado en un lecho de roca, el mineral estuvo durante mucho tiempo protegido de estos elementos en Becker’s Quarry en Willington, Connecticut. Pero cuando JJ Mottes Company comenzó a abastecerse de piedra del sitio a principios de la década de 1980, el proveedor, sin saberlo, introdujo la pirrotita en las fuerzas naturales que causan su descomposición.

Como ocurre hoy, muchos factores podrían haber contribuido al desmoronamiento de los cimientos, como cambios de temperatura, drenaje deficiente o reacciones álcali-sílice, otro fenómeno químico que puede degradar el hormigón desde dentro. “No es sorprendente que el concreto se agriete”, dijo Wille. Nadie relacionó definitivamente esta forma de falla estructural en Connecticut con la pirrotita hasta la década de 2000.

In 2016, after Wille and a graduate student on his team discovered pyrrhotite in core samples from concrete basement walls, they attributed the crumbling concrete to sulfate attacks. By the next year, the state had received more than 550 reports of homes with failing foundations, and it later determined tens of thousands more were at risk, as the concrete originated from the widely used JJ Mottes Company up through 2015. “Originally, we just kind of assumed this is the only quarry that was involved,” said Nick Scaglione, the president of Concrete Research & Testing, a laboratory in Ohio that identified pyrrhotite reactions as the cause of cracking in Connecticut back in 2008.

En 2016, después de que Wille y un estudiante de posgrado de su equipo descubrieran pirrotita en muestras de núcleos de paredes de hormigón del sótano, atribuyeron el hormigón desmoronado a ataques de sulfato. Para el año siguiente, el estado había recibido más de 550 informes de casas con cimientos defectuosos, y luego determinó que decenas de miles más estaban en riesgo, ya que el concreto procedía de la ampliamente utilizada JJ Mottes Company hasta 2015. “Originalmente, Simplemente supuse que esta era la única cantera involucrada”, dijo Nick Scaglione, presidente de Concrete Research & Testing, un laboratorio en Ohio que identificó en 2018 reacciones de pirrotita como la causa del agrietamiento en Connecticut.

Por esa época, y sin que muchos en Connecticut lo supieran, cientos de propietarios de viviendas en Quebec, Canadá, estaban en medio de su propia batalla prolongada con la pirrotita y una empresa constructora. Un geólogo de la sociedad entonces conocida como SNC-Lavalin, hoy AtkinsRéalis, había aprobado el uso de hormigón contaminado con el mineral, que los constructores utilizaron en miles de viviendas. El hormigón agrietado se manifestó más rápidamente que en Connecticut, y con el apoyo financiero insuficiente disponible, algunas familias cayeron en la ruina financiera. “Fue una pesadilla”, dijo Alain Gélinas, que encabeza una coalición que representa a otras víctimas de la pirrotita.

Gélinas descubrió grietas en su sótano en 2012. Unos años más tarde, viajó a Connecticut para reunirse con un grupo de propietarios. Le sorprendieron las similitudes en sus situaciones, específicamente cómo una empresa podía ser responsable de tanto sufrimiento. “Fue un copiar y pegar de lo que pasamos aquí”, dijo Gélinas.

En Massachusetts, muchos pronto comenzarían a ver la misma grieta reveladora en sus cimientos. Al igual que en otras áreas con problemas documentados de pirrotita, Massachusetts reembolsa al menos parcialmente a los propietarios elegibles que solicitan pruebas a contratistas.

Pero Wille y otros investigadores todavía están perfeccionando esas pruebas. En la Universidad de Connecticut, por ejemplo, están estudiando cómo cantidades específicas del mineral se relacionan con futuros daños al concreto, parte de un esfuerzo global para comprender por qué los cimientos se están desmoronando en América del Norte y más allá.

En mayo pasado, alrededor de 75 científicos, consultores, constructores y otros expertos se reunieron en el campus de la Universidad Laval en la ciudad de Quebec para la primera Conferencia Internacional sobre Reacciones del Sulfuro de Hierro en el Concreto.

Durante cuatro días, los investigadores discutieron todo, desde los avances en las pruebas de muestras electroquímicas hasta un mapeo geológico amplio. Algunos citaron el mapa de 2020 del Servicio Geológico de Estados Unidos, de áreas potenciales de roca con pirrotita, con una vasta veta que atraviesa las Montañas Apalaches. Pero tanto el coautor del informe, Jeff Mauk, como otros científicos adviertieron que el mapa no tiene en cuenta factores como la cantidad del mineral o su nivel de reactividad.

“Ese mapa puede ser realmente engañoso”, dijo Scaglione. “No miraría ese mapa y diría: ‘Vaya, podríamos tener un problema muy extendido aquí basado en este mapa’. No lo sabemos”.

Las pruebas de seguimiento en las canteras son vitales, afirmó Fecteau: “No puedes evitarlas si quieres estar seguro”.

Si bien los investigadores en la conferencia de la ciudad de Quebec asistieron de Japón, Noruega y Portugal, entre otros países, tendían a centrarse en el problema del hormigón agrietado en tres focos conocidos: Nueva Inglaterra, Quebec y, más recientemente, Irlanda.

Desde que obtuvo el reconocimiento público en 2013, una serie de edificios en ruinas en Irlanda es conocido como la crisis o escándalo de la mica. Un panel encargado por el gobierno irlandés atribuyó defectos estructurales en varios condados a la pirita y, más publicitada, a la mica moscovita, un mineral que absorbe agua. Cuando la mica se congela y se descongela, concluyó el panel, su tamaño fluctuante agita el hormigón circundante. Después de años de que los propietarios hicieran campaña para obtener apoyo, el gobierno inició un plan de subvenciones para ayudar a reconstruir las viviendas de las personas.

Pero en dos estudios recientes publicados en Cement and Concrete Research, los científicos informaron que la “revisión documental” del gobierno irlandés puede haber pasado por alto la causa principal de la crisis. La oxidación de la pirrotita, no la absorción de agua por parte de la mica, fue la que desintegró el hormigón, según mostraron sus análisis químicos del material de construcción. “Por el momento, todo el plan se basa en pruebas para detectar algo incorrecto”, dijo Paul Dunlop, glaciólogo de la Universidad de Ulster y coautor de los estudios después de que un ingeniero le dijera que sus paredes dieron positivo en pirrotita.

En la ciudad de Quebec, Dunlop compartió los descubrimientos de su equipo y encontró investigadores con enfoques similares en Canadá, Estados Unidos y otros países. “Se ven exactamente los mismos minerales de sulfato secundario que se producen en otros hormigones de todo el mundo”, dijo. “Entonces, en cierto modo, es una especie de afirmación de que estás en el camino correcto”.

La conferencia confirmó que los propietarios de viviendas afectados en Massachusetts, como Loglisci, también estaban en lo cierto. En un resumen escrito de una de las presentaciones de la conferencia, Scaglione y un colega informaron que el agregado contaminado con pirrotita en al menos una base de Massachusetts que se estaba desmoronando era “litológicamente distinta” del agregado encontrado en Connecticut. No procedía de una cantera de allí, sino de una de Rutland, Massachusetts.

Pero incluso cuando el problema se extendió a los condados más cercanos a la Cámara de Representantes del Estado de Massachusetts en Boston, la legislación para apoyar a los propietarios de viviendas siguió siendo difícil de alcanzar. A principios de este año, los legisladores eliminaron de la Ley de Viviendas Asequibles del estado un plan para brindar ayuda financiera similar al de Connecticut. El 30 de octubre, miembros de Residentes de Massachusetts contra los cimientos en ruinas visitaron Beacon Hill para abogar, una vez más, por ayuda financiera.

“Después de siete años de luchar por esto, eso te desgasta”, dijo Loglisci, “y simplemente te frustras y solo quieres que alguien haga algo, que realmente haga algo”.

Los científicos están realizando más investigaciones sobre cómo la cantidad de pirrotita, las diferentes variedades del mineral y el contenido de agua en el hormigón afectan el daño a los cimientos. Mientras tanto, las familias sólo pueden adivinar cuánto tiempo sus cimientos en ruinas soportarán sus muros.

Por ahora, Karen Bilotti y su familia están postergando la idea de reemplazar los suyos. Recibieron un presupuesto de 300.000 dólares para levantar una casa que les costó 500.000 dólares. No pueden afrontarlo.

“Me gustaría tener un árbol del dinero creciendo en mi patio trasero” -dijo-, “pero no lo tengo”.

Lo que alguna vez fue la casa de sus sueños es ahora, como dijo Bilotti, “una pesadilla”. A diferencia del tornado, este problema los persigue todos los días. “Creo que esto es casi peor”, dijo. “Porque no hay un final a la vista”.

Benjamin Cassidy es un periodista radicado en Nueva Inglaterra cuyo trabajo ha aparecido en Scientific American, National Geographic, Nautilus y Smithsonian, entre otras publicaciones. Este artículo fue publicado originalmente en Undark. Lea el artículo original.

English version #

Benjamin Cassidy wrote in EOS that Karen Bilotti and her husband, Sam, started to notice fine lines in their basement’s concrete walls. Ordinarily, they might not have given them a second thought. But the Bilottis had recently heard about a growing group of nearby homeowners in Massachusetts with larger cracks in their foundations, and Sam began to worry.

“‘With our luck, our house is probably affected,’” Karen recalled him saying. “And I’m like, ‘You’re crazy. You’re absolutely ridiculous. There’s no way.’”

Through core testing, scientists and engineers had determined the culprit behind fissures like those in their neighbors’ homes was pyrrhotite, a mineral made up of sulfur and iron found in some concrete aggregates. When exposed to air and water, pyrrhotite can break down into secondary minerals that cause foundations to fracture, structural integrity to erode, and home values to tank.

“It’s like your house was diagnosed with cancer,” said Michelle Loglisci, a founder of Massachusetts Residents Against Crumbling Foundations, a grassroots organization of homeowners fighting for legislation and financial relief in their state.

It wasn’t the first time the Bilottis had faced a housing catastrophe. Back in 2011, a tornado tore through Western and Central Massachusetts, corkscrewing the frame of their previous home off the foundation like a twisted dollhouse.

The Bilottis didn’t want to rebuild. So they bought a home in another part of town—“our dream house,” Bilotti said—thinking they’d put their bad fortune behind them. And now that dream home faced an uncertain future.

Sure enough, a test revealed they were positive for pyrrhotite. Like scores of other Massachusetts homeowners, they faced a grim decision: live with the knowledge that their house’s foundation was gradually failing, or pay as much as $300,000 to replace it without any guarantee of future support from the state.

For years, public officials in the U.S. associated this real estate nightmare with Connecticut, where investigators attributed one quarry’s pyrrhotite-contaminated aggregate to as many as 35,000 faulty foundations in the state. But the increasingly sprawling reports of crumbling foundations in Massachusetts have heightened concern among scientists and homeowner advocates that defective concrete is a more widespread problem—one with little current or historical oversight—than previously understood. Recently, a condo complex with a cracking foundation in Dracut, Massachusetts, just south of the New Hampshire border, tested positive for pyrrhotite. Beyond New England, pyrrhotite from two known quarries in Canada has damaged thousands of homes since the 1990s, and studies over the past two years revealed its deteriorative effects as far as Ireland.

The discoveries in these regions have undergirded a nascent area of scientific inquiry. Last May, the first International Conference on Iron Sulfide Reactions in Concrete included presentations on testing for pyrrhotite, understanding its reactivity, and mapping the mineral. The pre-Conference call. And the post-conference results

The conference, too, revealed a quarry in Massachusetts that had tested positive for pyrrhotite. Some researchers think there may be more: “There have to be other quarries,” said Kay Wille, principal investigator of the University of Connecticut’s Crumbling Concrete Research and Testing team.

Without widespread enforced testing for pyrrhotite, scientists can’t determine the extent of defective concrete, or how to contain its spread. “It may happen everywhere if you don’t have the regulation to ensure it doesn’t happen,” said Pierre-Luc Fecteau, a researcher at Université Laval who helped organize the conference in Canada.

To clear high regulatory bars, concrete suppliers typically “test for everything,” said Craig Dauphinais, executive director of the Massachusetts Concrete & Aggregate Producers Association, a trade group that represents the concrete industry in Massachusetts and Rhode Island. But Connecticut didn’t require quarries to report sulfur content and, in some cases, pyrrhotite until 2022, and Massachusetts only passed a law requiring quarries to test for sulfur compounds in 2023, though testing has not yet started, said John Goggin, a communications analyst at the Massachusetts Department of Transportation. Until Connecticut traced its cracking foundations back to a concrete supplier in its state, pyrrhotite wasn’t on the industry’s radar, according to Dauphinais.

“Nobody knew about this mineral,” he said. “Nobody knew that there was an issue with it related to ready-mix concrete.”

Pyrrhotite is easy to overlook. The bronze mineral remains less prevalent than pyrite, a fellow iron sulfide known as fool’s gold. But like its lucrative-looking kin, the uncommon mineral has become known for its deception—for blending into sturdy concrete while, very gradually, crumbling it.

Pyrrhotite doesn’t cause this deterioration by itself. When the highly reactive iron sulfide encounters water and oxygen, it transforms into sulfate minerals—ettringite, thaumasite, and gypsum—that occupy more space than the pyrrhotite they’re replacing. This expansion in volume pressures the surrounding mix of aggregate, cement, and water in concrete, forcing it to crack. This phenomenon is called an internal sulfate attack.

“It’s like a process which is very difficult, challenging to slow down or to stop or prevent,” Wille said.

For a long time, the attack happens under the surface and can take anywhere from 10 to 30 years for cracks to appear. But once the splintering starts, Wille explained, the concrete’s degradation accelerates, as the fissures expose pyrrhotite to more moisture and oxygen.

Entrenched in bedrock, the mineral was long protected from these elements at Becker’s Quarry in Willington, Connecticut. But when the JJ Mottes Company started sourcing stone from the site in the early 1980s, the supplier unwittingly introduced pyrrhotite to the natural forces that cause it to break down.

As is the case today, many factors could have contributed to crumbling foundations, such as temperature changes, poor drainage, or alkali-silica reactions, another chemical phenomenon that can degrade concrete from within. “It’s not surprising if concrete cracks,” Wille said. No one definitively connected this form of structural failure in Connecticut to pyrrhotite until the 2000s.

In 2016, after Wille and a graduate student on his team discovered pyrrhotite in core samples from concrete basement walls, they attributed the crumbling concrete to sulfate attacks. By the next year, the state had received more than 550 reports of homes with failing foundations, and it later determined tens of thousands more were at risk, as the concrete originated from the widely used JJ Mottes Company up through 2015. “Originally, we just kind of assumed this is the only quarry that was involved,” said Nick Scaglione, the president of Concrete Research & Testing, a laboratory in Ohio that identified pyrrhotite reactions as the cause of cracking in Connecticut back in 2008.

Around that time, and unbeknownst to many in Connecticut, hundreds of homeowners in Quebec, Canada were in the middle of their own protracted battle with pyrrhotite and a construction company. A geologist from the corporation then known as SNC-Lavalin, now AtkinsRéalis, had approved the use of concrete contaminated with the mineral, which builders then used in thousands of homes. The crumbling concrete manifested more rapidly than in Connecticut, and with insufficient financial support available, some families fell into financial ruin. “It was a nightmare,” said Alain Gélinas, who heads a coalition representing fellow victims of pyrrhotite.

Gélinas discovered cracks in his basement in 2012. A few years later, he traveled to Connecticut to meet with a group of homeowners. He was struck by the similarities in their plights, specifically how one company could be responsible for so much suffering. “It was a copy and paste of what we went through here,” Gélinas said.

In Massachusetts, many would soon start to see the same telltale cracking in their foundations. Like in other areas with documented pyrrhotite problems, Massachusetts at least partially reimburses eligible homeowners who order tests from contractors.

But Wille and other researchers are still refining those tests. At the University of Connecticut, for instance, they’re studying how specific quantities of the mineral relate to future concrete damage, part of a global effort to understand why foundations are crumbling in North America, and beyond.

Last May, about 75 scientists, consultants, builders, and other experts gathered on the campus of Université Laval in Quebec City for the first International Conference on Iron Sulfide Reactions in Concrete.

Over four days, researchers discussed everything from advances in electrochemical sample testing to broad geological mapping. Some cited the 2020 U. S. Geological Survey map of potential areas of rock with pyrrhotite, with a vast vein running through the Appalachian Mountains. But both the report’s co-author, Jeff Mauk, and other scientists caution that the map doesn’t account for factors such as the amount of the mineral or its reactivity level.

“That map can be really kind of misleading,” said Scaglione. “I would not look at that map and say, ‘Wow, we could have a really widespread problem here based on this map.’ We don’t know.”

Follow-up testing at quarries is vital, said Fecteau: “You can’t get around that if you want to be sure.”

While researchers at the Quebec City conference hailed from Japan and Norway and Portugal, among other countries, they tended to focus on the problem of crumbling concrete in three known hotbeds: New England, Quebec, and, of more recent concern, Ireland.

Since gaining public recognition in 2013, a spate of crumbling buildings in Ireland has been known as the mica crisis or scandal. A panel commissioned by the Irish government attributed structural defects in multiple counties to pyrite and, more widely publicized, muscovite mica, a mineral that absorbs water. When the mica freezes and thaws, the panel concluded, its fluctuating size roils the surrounding concrete. After years of property owners campaigning for support, the government started a grant scheme to help rebuild people’s homes.

But in two recent studies published in Cement and Concrete Research, scientists reported that the Irish government’s “desktop review” may have overlooked the primary cause of the crisis. Pyrrhotite oxidation, not mica’s absorption of water, was driving the concrete apart, their chemical analyses of building material showed. “At the moment, the entire scheme is based on testing for the wrong thing,” said Paul Dunlop, a glaciologist at Ulster University who co-authored the studies after an engineer told him his walls tested positive for pyrrhotite.

In Quebec City, Dunlop shared his team’s discoveries and found researchers with similar focuses in Canada, the U.S., and other countries. “You see the exact same secondary sulfate minerals being produced elsewhere in other concretes around the world,” he said. “So, in a way, it’s sort of affirmation that you’re on the right track.”

The conference confirmed affected homeowners in Massachusetts like Loglisci were on to something, too. In a written abstract of one of the conference presentations, Scaglione and a colleague reported that pyrrhotite-contaminated aggregate in at least one crumbling Massachusetts foundation was “lithologically distinct” from the aggregate found in Connecticut. It didn’t come from the quarry there but one in Rutland, Massachusetts.

But even as the problem crept into counties closer to the Massachusetts State House in Boston, legislation to support homeowners remained elusive. Earlier this year, lawmakers stripped away a plan to provide financial relief akin to Connecticut’s from the state’s Affordable Homes Act. On Oct. 30, members of the Massachusetts Residents Against Crumbling Foundations visited Beacon Hill to advocate, once again, for financial relief.

“After seven years of fighting for this, it wears on you,” Loglisci said, “and you just get frustrated, and you just want somebody to do something—to actually do something.”

Scientists are conducting further research on how the amount of pyrrhotite, the different varieties of the mineral, and the water content in concrete affect the damage to foundations. In the meantime, families can only guess how long their crumbling foundations will support their walls.

For now, Karen Bilotti and her family are holding off on replacing theirs. They received a $300,000 estimate to lift a house that cost them $500,000. They can’t afford it.

“I wish I had a money tree growing in my backyard,” she said, “but I do not.”

What was once their dream home is now, as Bilotti put it, “a nightmare.” Unlike the tornado, it haunts them every day. “This, I think, is almost worse,” she said. “Because there’s no end in sight.”

Benjamin Cassidy is a New England-based journalist whose work has appeared in Scientific American, National Geographic, Nautilus, and Smithsonian, among other publications.

This article was originally published on Undark. Read the original article.