Científicos del MIT descubren el origen de una ráfaga rápida de radio

Table of Contents

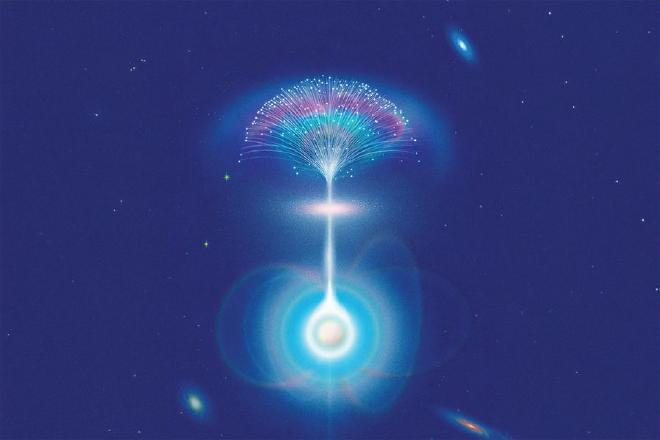

Es probable que los fugaces fuegos artificiales cósmicos surgieran de la turbulenta magnetosfera que rodea a una lejana estrella de neutrones.

Las ráfagas rápidas de radio son breves y brillantes explosiones de ondas de radio emitidas por objetos extremadamente compactos, como estrellas de neutrones y, posiblemente, agujeros negros. Estos fuegos artificiales fugaces duran sólo una milésima de segundo y pueden transportar una enorme cantidad de energía, suficiente para eclipsar brevemente a galaxias enteras.

Desde que en 2007 se descubrió la primera ráfaga rápida de radio (FRB, por sus siglas en inglés), los astrónomos han detectado miles de FRB, cuyas ubicaciones varían desde dentro de nuestra propia galaxia, la Vía Láctea, hasta a 8 mil millones de años luz de distancia. La forma exacta en que se generan estas llamaradas cósmicas de radio es una incógnita muy controvertida.

Ahora, los astrónomos del MIT han descubierto el origen de al menos una ráfaga rápida de radio utilizando una técnica novedosa que podría hacer lo mismo con otras FRB. En su nuevo estudio, que se publicó en la revista Nature, el equipo se centró en la FRB 20221022A, una ráfaga rápida de radio descubierta previamente que se detectó en una galaxia a unos 200 millones de años luz de distancia.

El equipo se concentró más en determinar la ubicación precisa de la señal de radio analizando su “parpadeo, similar a cómo titilan las estrellas en el cielo nocturno. Los científicos estudiaron los cambios en el brillo de la FRB y determinaron que la explosión debe haberse originado en las inmediaciones de su fuente, en lugar de una mayor distancia, como predijeron algunos modelos.

El equipo estima que FRB 20221022A estalló en una región que está extremadamente cerca de una estrella de neutrones en rotación, a 10.000 kilómetros de distancia como máximo. Eso es menos que la distancia entre Nueva York y Singapur. A tan corta distancia, la explosión probablemente surgió de la magnetosfera de la estrella de neutrones, una región altamente magnética que rodea inmediatamente a la estrella ultracompacta.

Los hallazgos del equipo proporcionan la primera evidencia concluyente de que una ráfaga de radio rápida puede originarse en la magnetosfera, el entorno altamente magnético que rodea inmediatamente a un objeto extremadamente compacto.

“En estos entornos de estrellas de neutrones, los campos magnéticos están realmente en los límites de lo que el universo puede producir”, afirmó la autora principal Kenzie Nimmo, investigadora posdoctoral en el Instituto Kavli de Astrofísica e Investigación Espacial del MIT. “Ha habido mucho debate sobre si esta brillante emisión de radio podría siquiera escapar de ese plasma extremo”.

“Alrededor de estas estrellas de neutrones altamente magnéticas, también conocidas como magnetares, los átomos no pueden existir; simplemente se desintegrarían por los campos magnéticos”, afirmó Kiyoshi Masui, profesor asociado de física en el MIT. “Lo interesante aquí es que hemos descubierto que la energía almacenada en esos campos magnéticos, cerca de la fuente, se está retorciendo y reconfigurando de tal manera que puede ser liberada en forma de ondas de radio que podemos ver al otro lado del universo”.

Los coautores del estudio del MIT incluyen a Adam Lanman, Shion Andrew, Daniele Michilli y Kaitlyn Shin, junto con colaboradores de múltiples instituciones.

Tamaño de la ráfaga #

Las detecciones de ráfagas rápidas de radio han aumentado en los últimos años gracias al Canadian Hydrogen Intensity Mapping Experiment (CHIME). El conjunto de radiotelescopios consta de cuatro grandes receptores estacionarios, cada uno con forma de medio tubo, que están sintonizados para detectar emisiones de radio dentro de un rango que es muy sensible a las ráfagas rápidas de radio.

Desde 2020, CHIME ha detectado miles de FRB en todo el universo. Si bien los científicos generalmente coinciden en que las ráfagas surgen de objetos extremadamente compactos, no está claro cuál es la física exacta que las impulsa. Algunos modelos predicen que las ráfagas rápidas de radio deberían provenir de la magnetosfera turbulenta que rodea inmediatamente a un objeto compacto, mientras que otros predicen que las ráfagas deberían originarse mucho más lejos, como parte de una onda de choque que se propaga lejos del objeto central.

Para distinguir entre los dos escenarios y determinar dónde surgen las ráfagas rápidas de radio, el equipo consideró el titileo, el efecto que se produce cuando la luz de una fuente pequeña y brillante, como una estrella, se filtra a través de algún medio, como el gas de una galaxia. A medida que la luz de la estrella se filtra a través del gas, se dobla de maneras que hacen que parezca, para un observador distante, como si la estrella estuviera titilando. Cuanto más pequeño o más lejano es un objeto, más titila. La luz de objetos más grandes o más cercanos, como los planetas de nuestro propio sistema solar, experimenta menos curvatura y, por lo tanto, no parece titilar.

El equipo razonó que si pudieran estimar el grado en que centellea una FRB, podrían determinar el tamaño relativo de la región de donde se originó. Cuanto más pequeña sea la región, más cerca estará la explosión de su fuente y más probable es que provenga de un entorno magnéticamente turbulento. Cuanto más grande sea la región, más lejos estará la explosión, lo que respalda la idea de que las FRB provienen de ondas de choque lejanas.

Patrón de titilado #

Para probar su idea, los investigadores observaron FRB 20221022A, una ráfaga de radio rápida que fue detectada por CHIME en 2022. La señal dura unos dos milisegundos y es una FRB relativamente común y corriente en términos de brillo. Sin embargo, los colaboradores del equipo en la Universidad McGill descubrieron que la FRB 20221022A exhibía una propiedad destacada: la luz de la ráfaga estaba altamente polarizada, con un ángulo de polarización que trazaba una curva suave en forma de S. Este patrón se interpreta como evidencia de que el sitio de emisión de la FRB está rotando, una característica observada previamente en los púlsares, que son estrellas de neutrones altamente magnetizadas y rotatorias.

Fue la primera vez que se observó una polarización similar en ráfagas rápidas de radio, lo que sugiere que la señal podría haber surgido de las inmediaciones de una estrella de neutrones. Los resultados del equipo de McGill se publicaron en un artículo complementario en Nature.

El equipo del MIT se dio cuenta de que si FRB 20221022A se originó cerca de una estrella de neutrones, deberían poder demostrarlo mediante el titilado.

En su nuevo estudio, Nimmo y sus colegas analizaron datos de CHIME y observaron variaciones pronunciadas en el brillo que indicaban centelleo; en otras palabras, el FRB estaba titilando. Confirmaron que hay gas en algún lugar entre el telescopio y el FRB que está doblando y filtrando las ondas de radio. Luego, el equipo determinó dónde podría estar ubicado este gas, lo que confirmó que el gas dentro de la galaxia anfitriona del FRB era responsable de parte del centelleo observado. Este gas actuó como una lente natural, lo que permitió a los investigadores acercarse al sitio del FRB y determinar que el estallido se originó en una región extremadamente pequeña, estimada en unos 10.000 kilómetros de ancho.

“Esto significa que la FRB probablemente se encuentra a cientos de miles de kilómetros de la fuente”, indicó Nimmo. “Eso es muy cerca. A modo de comparación, esperaríamos que la señal estuviera a más de decenas de millones de kilómetros de distancia si se originara a partir de una onda de choque, y no veríamos centelleo alguno”.

“Acercarse a una región de 10.000 kilómetros, desde una distancia de 200 millones de años luz, es como poder medir el ancho de una hélice de ADN, que tiene unos 2 nanómetros de ancho, en la superficie de la Luna”, afirmó Masui. “Hay una gama asombrosa de escalas involucradas”.

Los resultados del equipo, combinados con los hallazgos del equipo de McGill, descartan la posibilidad de que FRB 20221022A surgiera de las afueras de un objeto compacto. En cambio, los estudios demuestran por primera vez que las ráfagas rápidas de radio pueden originarse muy cerca de una estrella de neutrones, en entornos magnéticos altamente caóticos.

“Estas explosiones ocurren constantemente y CHIME detecta varias al día”, afirmó Masui. “Puede haber mucha diversidad en cómo y dónde ocurren, y esta técnica de centelleo será realmente útil para ayudar a desentrañar los diversos mecanismos físicos que impulsan estas explosiones”.

“El patrón trazado por el ángulo de polarización era tan sorprendentemente similar al observado en los púlsares de nuestra propia galaxia, la Vía Láctea, que al principio hubo cierta preocupación de que la fuente no fuera en realidad una FRB, sino un púlsar mal clasificado”, afirmó Ryan Mckinven, coautor del estudio de la Universidad McGill. “Afortunadamente, estas preocupaciones se disiparon con la ayuda de los datos recopilados con un telescopio óptico que confirmó que la FRB se originó en una galaxia a millones de años luz de distancia”.

“La polarimetría es una de las pocas herramientas que tenemos para investigar estas fuentes distantes”, explicó Mckinven. “Este resultado probablemente inspirará estudios de seguimiento de comportamiento similar en otras FRB y estimulará esfuerzos teóricos para conciliar las diferencias en sus señales polarizadas”.

-

Esta investigación fue apoyada por varias instituciones, entre ellas la Fundación Canadiense para la Innovación, el Instituto Dunlap de Astronomía y Astrofísica de la Universidad de Toronto, el Instituto Canadiense de Investigación Avanzada, el Instituto Espacial Trottier de la Universidad McGill y la Universidad de Columbia Británica.

-

El paper Magnetospheric origin of a fast radio burst constrained using scintillation, fue publicado en Nature. Autores: Kenzie Nimmo, Ziggy Pleunis, Paz Beniamini, Pawan Kumar, Adam E. Lanman, D. Z. Li, Robert Main, Mawson W. Sammons, Shion Andrew, Mohit Bhardwaj, Shami Chatterjee, Alice P. Curtin, Emmanuel Fonseca, B. M. Gaensler, Ronniy C. Joseph, Zarif Kader, Victoria M. Kaspi, Mattias Lazda, Calvin Leung, Kiyoshi W. Masui, Ryan Mckinven, Daniele Michilli, Ayush Pandhi, Aaron B. Pearlman, Masoud Rafiei-Ravandi, Ketan R. Sand, Kaitlyn Shin, Kendrick Smith & Ingrid H. Stairs

-

El paper de McGill A pulsar-like polarization angle swing from a nearby fast radio burst también fue publicado en Nature. Autores: Ryan Mckinven, Mohit Bhardwaj, Tarraneh Eftekhari, Charles D. Kilpatrick, Aida Kirichenko, Arpan Pal, Amanda M. Cook, B. M. Gaensler, Utkarsh Giri, Victoria M. Kaspi, Daniele Michilli, Kenzie Nimmo, Aaron B. Pearlman, Ziggy Pleunis, Ketan R. Sand, Ingrid Stairs, Bridget C. Andersen, Shion Andrew, Kevin Bandura, Charanjot Brar, Tomas Cassanelli, Shami Chatterjee, Alice P. Curtin, Fengqiu Adam Dong, Gwendolyn Eadie, Emmanuel Fonseca, Adaeze L. Ibik, Jane F. Kaczmarek, Bikash Kharel, Mattias Lazda, Calvin Leung, Dongzi Li, Robert Main, Kiyoshi W. Masui, Juan Mena-Parra, Cherry Ng, Ayush Pandhi, Swarali Shivraj Patil, J. Xavier Prochaska, Masoud Rafiei-Ravandi, Paul Scholz, Vishwangi Shah, Kaitlyn Shin & Kendrick Smith

-

El artículo MIT scientists pin down the origins of a fast radio burst, signed by Jennifer Chu, fue publicado en la sección de noticias del MIT.

English version #

MIT scientists pin down the origins of a fast radio burst #

The fleeting cosmic firework likely emerged from the turbulent magnetosphere around a far-off neutron star.

Fast radio bursts are brief and brilliant explosions of radio waves emitted by extremely compact objects such as neutron stars and possibly black holes. These fleeting fireworks last for just a thousandth of a second and can carry an enormous amount of energy — enough to briefly outshine entire galaxies.

Since the first fast radio burst (FRB) was discovered in 2007, astronomers have detected thousands of FRBs, whose locations range from within our own galaxy to as far as 8 billion light-years away. Exactly how these cosmic radio flares are launched is a highly contested unknown.

Now, astronomers at MIT have pinned down the origins of at least one fast radio burst using a novel technique that could do the same for other FRBs. In their new study, published in the journal Nature, the team focused on FRB 20221022A — a previously discovered fast radio burst that was detected from a galaxy about 200 million light-years away.

The team zeroed in further to determine the precise location of the radio signal by analyzing its “scintillation,” similar to how stars twinkle in the night sky. The scientists studied changes in the FRB’s brightness and determined that the burst must have originated from the immediate vicinity of its source, rather than much further out, as some models have predicted.

The team estimates that FRB 20221022A exploded from a region that is extremely close to a rotating neutron star, 10,000 kilometers away at most. That’s less than the distance between New York and Singapore. At such close range, the burst likely emerged from the neutron star’s magnetosphere — a highly magnetic region immediately surrounding the ultracompact star.

The team’s findings provide the first conclusive evidence that a fast radio burst can originate from the magnetosphere, the highly magnetic environment immediately surrounding an extremely compact object.

“In these environments of neutron stars, the magnetic fields are really at the limits of what the universe can produce,” said lead author Kenzie Nimmo, a postdoc in MIT’s Kavli Institute for Astrophysics and Space Research. “There’s been a lot of debate about whether this bright radio emission could even escape from that extreme plasma.”

“Around these highly magnetic neutron stars, also known as magnetars, atoms can’t exist — they would just get torn apart by the magnetic fields,” explained Kiyoshi Masui, associate professor of physics at MIT. “The exciting thing here is, we find that the energy stored in those magnetic fields, close to the source, is twisting and reconfiguring such that it can be released as radio waves that we can see halfway across the universe.”

The study’s MIT co-authors include Adam Lanman, Shion Andrew, Daniele Michilli, and Kaitlyn Shin, along with collaborators from multiple institutions.

Burst size #

Detections of fast radio bursts have ramped up in recent years, due to the Canadian Hydrogen Intensity Mapping Experiment (CHIME). The radio telescope array comprises four large, stationary receivers, each shaped like a half-pipe, that are tuned to detect radio emissions within a range that is highly sensitive to fast radio bursts.

Since 2020, CHIME has detected thousands of FRBs from all over the universe. While scientists generally agree that the bursts arise from extremely compact objects, the exact physics driving the FRBs is unclear. Some models predict that fast radio bursts should come from the turbulent magnetosphere immediately surrounding a compact object, while others predict that the bursts should originate much further out, as part of a shockwave that propagates away from the central object.

To distinguish between the two scenarios, and determine where fast radio bursts arise, the team considered scintillation — the effect that occurs when light from a small bright source such as a star, filters through some medium, such as a galaxy’s gas. As the starlight filters through the gas, it bends in ways that make it appear, to a distant observer, as if the star is twinkling. The smaller or the farther away an object is, the more it twinkles. The light from larger or closer objects, such as planets in our own solar system, experience less bending, and therefore do not appear to twinkle.

The team reasoned that if they could estimate the degree to which an FRB scintillates, they might determine the relative size of the region from where the FRB originated. The smaller the region, the closer in the burst would be to its source, and the more likely it is to have come from a magnetically turbulent environment. The larger the region, the farther the burst would be, giving support to the idea that FRBs stem from far-out shockwaves.

Twinkle pattern #

To test their idea, the researchers looked to FRB 20221022A, a fast radio burst that was detected by CHIME in 2022. The signal lasts about two milliseconds, and is a relatively run-of-the-mill FRB, in terms of its brightness. However, the team’s collaborators at McGill University found that FRB 20221022A exhibited one standout property: The light from the burst was highly polarized, with the angle of polarization tracing a smooth S-shaped curve. This pattern is interpreted as evidence that the FRB emission site is rotating — a characteristic previously observed in pulsars, which are highly magnetized, rotating neutron stars.

To see a similar polarization in fast radio bursts was a first, suggesting that the signal may have arisen from the close-in vicinity of a neutron star. The McGill team’s results were reported in a companion paper in Nature.

The MIT team realized that if FRB 20221022A originated from close to a neutron star, they should be able to prove this, using scintillation.

In their new study, Nimmo and her colleagues analyzed data from CHIME and observed steep variations in brightness that signaled scintillation — in other words, the FRB was twinkling. They confirmed that there is gas somewhere between the telescope and FRB that is bending and filtering the radio waves. The team then determined where this gas could be located, confirming that gas within the FRB’s host galaxy was responsible for some of the scintillation observed. This gas acted as a natural lens, allowing the researchers to zoom in on the FRB site and determine that the burst originated from an extremely small region, estimated to be about 10,000 kilometers wide.

“This means that the FRB is probably within hundreds of thousands of kilometers from the source,” Nimmo said. “That’s very close. For comparison, we would expect the signal would be more than tens of millions of kilometers away if it originated from a shockwave, and we would see no scintillation at all.”

“Zooming in to a 10,000-kilometer region, from a distance of 200 million light years, is like being able to measure the width of a DNA helix, which is about 2 nanometers wide, on the surface of the moon,” stated Masui. “There’s an amazing range of scales involved.”

The team’s results, combined with the findings from the McGill team, rule out the possibility that FRB 20221022A emerged from the outskirts of a compact object. Instead, the studies prove for the first time that fast radio bursts can originate from very close to a neutron star, in highly chaotic magnetic environments.

“These bursts are always happening, and CHIME detects several a day,” Masui said. “There may be a lot of diversity in how and where they occur, and this scintillation technique will be really useful in helping to disentangle the various physics that drive these bursts.”

“The pattern traced by the polarization angle was so strikingly similar to that seen from pulsars in our own Milky Way Galaxy that there was some initial concern that the source wasn’t actually an FRB but a misclassified pulsar,” said Ryan Mckinven, a co-author of the study from McGill University. “Fortunately, these concerns were put to rest with the help of data collected from an optical telescope that confirmed the FRB originated in a galaxy millions of light-years away.”

“Polarimetry is one of the few tools we have to probe these distant sources,” Mckinven explained. “This result will likely inspire follow-up studies of similar behavior in other FRBs and prompt theoretical efforts to reconcile the differences in their polarized signals.”

-

This research was supported by various institutions including the Canada Foundation for Innovation, the Dunlap Institute for Astronomy and Astrophysics at the University of Toronto, the Canadian Institute for Advanced Research, the Trottier Space Institute at McGill University, and the University of British Columbia.

-

The paper Magnetospheric origin of a fast radio burst constrained using scintillation, was published in Nature. Authors: Kenzie Nimmo, Ziggy Pleunis, Paz Beniamini, Pawan Kumar, Adam E. Lanman, D. Z. Li, Robert Main, Mawson W. Sammons, Shion Andrew, Mohit Bhardwaj, Shami Chatterjee, Alice P. Curtin, Emmanuel Fonseca, B. M. Gaensler, Ronniy C. Joseph, Zarif Kader, Victoria M. Kaspi, Mattias Lazda, Calvin Leung, Kiyoshi W. Masui, Ryan Mckinven, Daniele Michilli, Ayush Pandhi, Aaron B. Pearlman, Masoud Rafiei-Ravandi, Ketan R. Sand, Kaitlyn Shin, Kendrick Smith & Ingrid H. Stairs

-

The McGill’s paper A pulsar-like polarization angle swing from a nearby fast radio burst was also published in Nature. Authors: Ryan Mckinven, Mohit Bhardwaj, Tarraneh Eftekhari, Charles D. Kilpatrick, Aida Kirichenko, Arpan Pal, Amanda M. Cook, B. M. Gaensler, Utkarsh Giri, Victoria M. Kaspi, Daniele Michilli, Kenzie Nimmo, Aaron B. Pearlman, Ziggy Pleunis, Ketan R. Sand, Ingrid Stairs, Bridget C. Andersen, Shion Andrew, Kevin Bandura, Charanjot Brar, Tomas Cassanelli, Shami Chatterjee, Alice P. Curtin, Fengqiu Adam Dong, Gwendolyn Eadie, Emmanuel Fonseca, Adaeze L. Ibik, Jane F. Kaczmarek, Bikash Kharel, Mattias Lazda, Calvin Leung, Dongzi Li, Robert Main, Kiyoshi W. Masui, Juan Mena-Parra, Cherry Ng, Ayush Pandhi, Swarali Shivraj Patil, J. Xavier Prochaska, Masoud Rafiei-Ravandi, Paul Scholz, Vishwangi Shah, Kaitlyn Shin & Kendrick Smith