Hallan la primera estrella binaria cerca del agujero negro supermasivo de nuestra galaxia

Table of Contents

“Los agujeros negros no son tan destructivos como pensábamos”, declaró Florian Peißker, investigador de la Universidad de Colonia (Alemania) y autor principal del estudio publicado en Nature Communications. Las estrellas binarias, parejas de estrellas que orbitan entre sí, son muy comunes en el universo, pero nunca antes habían sido detectadas cerca de un agujero negro supermasivo, donde la intensa gravedad puede hacer que los sistemas estelares sean inestables.

D9, punto de partida para nuevos descubrimientos. #

Este nuevo descubrimiento muestra que algunos sistemas binarios pueden prosperar brevemente, incluso en condiciones tan adversas. D9, como ha sido bautizada la estrella binaria recién descubierta, fue detectada justo a tiempo: se estima que tiene sólo 2,7 millones de años, y la fuerte fuerza gravitacional del agujero negro cercano probablemente hará que se fusione en una sola estrella en sólo un millón de años, un período de tiempo muy pequeño para un sistema tan joven.

“Esto proporciona sólo una pequeña ventana, en lo que son las escalas de tiempo cósmicas, para observar un sistema binario de este tipo, ¡y lo logramos!”, explica la coautora Emma Bordier, también investigadora de la Universidad de Colonia, que previamente estudió en ESO.

Creíamos que no nacerían estrellas cerca de agujeros negros supermasivos #

Durante muchos años, la comunidad científica también pensaba que el entorno extremo cercano a un agujero negro supermasivo impedía que se formaran nuevas estrellas en los alrededores. Varias estrellas jóvenes que se encuentran muy cerca de Sagitario A* han refutado esta suposición. El descubrimiento de la joven estrella binaria ahora muestra que incluso en estas duras condiciones pueden formarse parejas estelares. “El sistema D9 muestra signos claros de la presencia de gas y polvo alrededor de las estrellas, lo que sugiere que podría ser un sistema estelar muy joven que debe haberse formado en las proximidades del agujero negro supermasivo”, explicó el coautor Michal Zajaček, investigador de la Universidad de Masaryk (República Checa) y de la Universidad de Colonia.

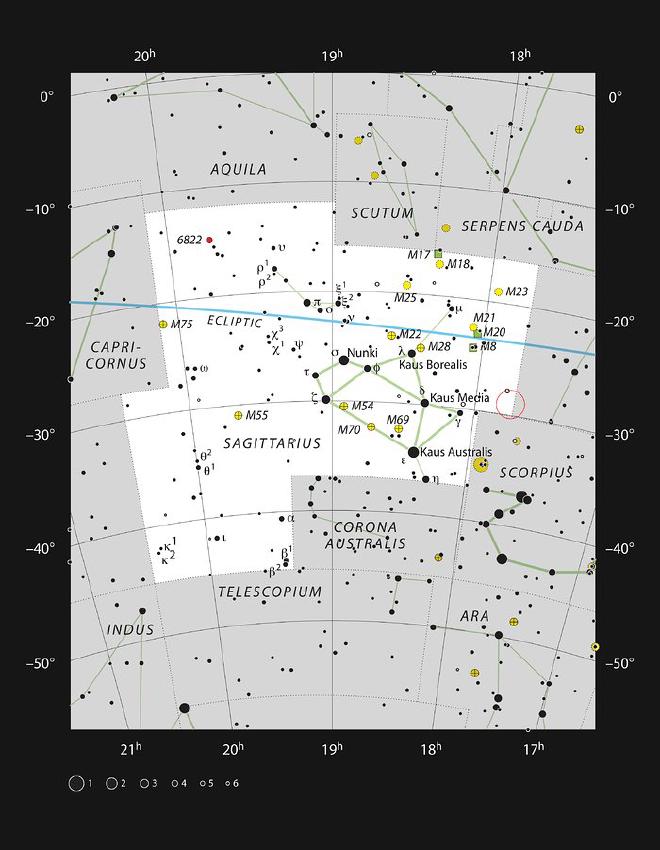

El sistema binario recién descubierto se encontró en un denso cúmulo de estrellas y otros objetos que orbitaban alrededor de Sagitario A*, llamado cúmulo S. Lo más enigmático de este cúmulo son los objetos G, que se comportan como estrellas pero parecen nubes de gas y polvo.

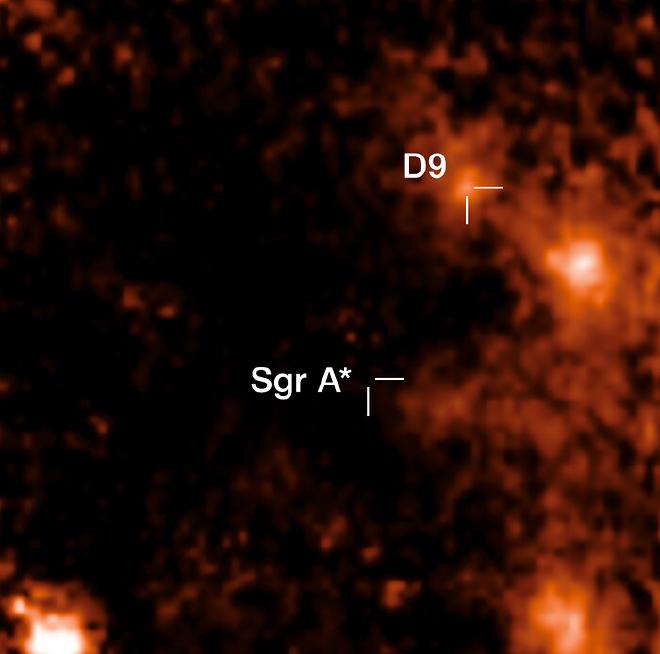

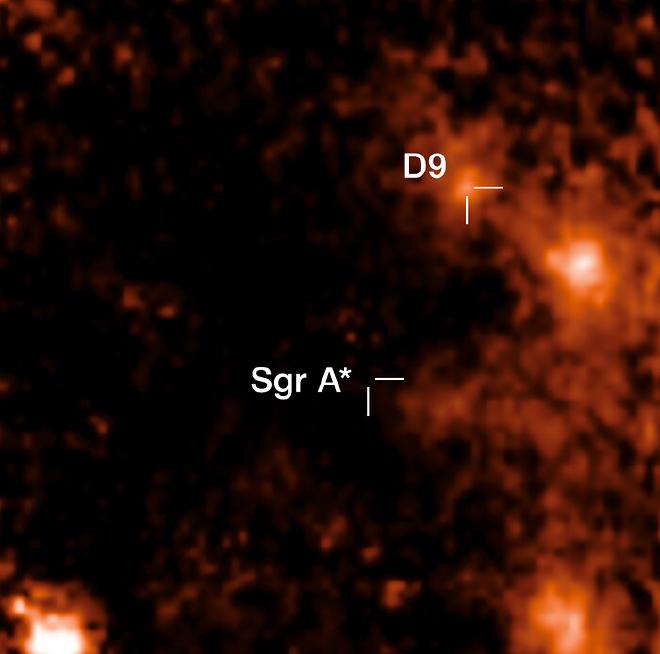

Mientras observaban estos misteriosos objetos, el equipo encontró un patrón sorprendente en D9. Los datos obtenidos con el instrumento ERIS del VLT, combinados con los datos de archivo del instrumento SINFONI, revelaron variaciones recurrentes en la velocidad de la estrella, lo que indica que D9 era en realidad dos estrellas orbitando entre sí. “Pensé que mi análisis estaba equivocado”, declaró Peißker, “pero el patrón espectroscópico abarcó unos 15 años, y estaba claro que esta detección es, de hecho, el primer sistema binario observado en el cúmulo S”.

Encontramos algo raro. Se han descubierto dos estrellas orbitando entre sí en las proximidades de Sgr A*, el agujero negro supermasivo situado en el centro de la Vía Láctea. La presencia de un joven sistema estelar binario que se forma y sobrevive en esta gravedad extrema implica que los agujeros negros no son tan destructivos como pensábamos. Este vídeo resume el descubrimiento. Crédito: ESO. Dirigido por: Angelos Tsaousis y Martin Wallner. Edición: Angelos Tsaousis. Apoyo técnico y en la web: Gurvan Bazin y Raquel Yumi Shida. Escrito por Hanna Huysegoms. Música: Stellardrone – Ethereal. Vídeos y fotos: ESO / Luis Calçada, Cristoph Malin (christophmalin.com), Martin Kornmesser, Florian Peißker et al., Nick Risinger (skysurvey.org), Schoedel, DSS, VISTA, EHT Collaboration, VVV Survey/D. Minniti Nogueras-Lara et al. Consultoras científicas: Paola Amico, Mariya Lyubenova.

Los resultados arrojan nueva información sobre lo que podrían ser los misteriosos objetos G1. El equipo propone que, en realidad, podrían ser una combinación de estrellas binarias que aún no se han fusionado y el material sobrante de estrellas ya fusionadas.

La danza de dos estrellas. La animación muestra cómo las dos estrellas del sistema estelar D9 orbitan entre sí, envueltas en una nube de gas y polvo. La línea azul indica la órbita del sistema binario alrededor de Sagitario A*, el agujero negro supermasivo ubicado en el centro de la Vía Láctea. D9 es la primera estrella binaria encontrada cerca de un agujero negro supermasivo. Su formación y supervivencia en este entorno extremo implican que los agujeros negros no son tan destructivos como pensábamos. Crédito: ESO/M. Kornmesser.

La naturaleza precisa de muchos de los objetos que orbitan alrededor de _Sagitario A_, así como la manera en que pudieron haberse formado tan cerca del agujero negro supermasivo, sigue siendo un misterio*. Pero esto podría cambiar pronto gracias a la actualización de GRAVITY+, instalado en el interferómetro del VLT y al instrumento METIS, en el Extremely Large Telescope (ELT) de ESO, que se está construyendo en Chile. Ambas instalaciones permitirán al equipo llevar a cabo observaciones aún más detalladas del centro galáctico, revelando la naturaleza de los objetos conocidos y, sin duda, descubriendo más estrellas binarias y sistemas jóvenes. “Nuestro descubrimiento nos permite especular sobre la presencia de planetas, ya que a menudo se forman alrededor de estrellas jóvenes. Parece plausible que la detección de planetas en el centro galáctico sea solo cuestión de tiempo”, concluyó Peißker.

Acercamiento al inesperado sistema binario D9. La animación muestra a D9, el primer par de estrellas descubierto cerca de Sagitario A*, el agujero negro supermasivo situado en el centro de la Vía Láctea. Nos acercamos y alejamos del agujero negro y de las estrellas individuales que lo orbitan, para luego acercarnos a D9, el primer sistema estelar binario encontrado en su vecindad. El vídeo, que fue realizado por un artista del Observatorio y Planetario de Brno, muestra cómo el sistema estelar orbita el agujero negro. También revela la nube de gas polvoriento en la que está envuelta la pareja de estrellas, lo que sugiere que se trata de un sistema estelar joven. La formación y supervivencia de un sistema estelar binario en este entorno extremo implican que los agujeros negros no son tan destructivos como pensábamos. Esta animación fue posible gracias a una beca Junior Star de la Fundación Checa de Ciencias (GM24-10599M). Crédito: P. Karas (Brno Observatory and Planetarium), RSA Cosmos Sky Explorer. Reconocimientos: M. Zajaček, F. Peißker and Czech Science Foundation.

- El paper “A binary system in the S cluster close to the supermassive black hole Sagittarius A”* fue publicado hoy en Nature Communications (doi: 10.1038/s41467-024-54748-3). El equipo está conformado por: F. Peißker (Instituto de Física I, Universidad de Colonia, Alemania [Universidad de Colonia]); M. Zajaček (Departamento de Física Teórica y Astrofísica, Universidad Masaryk, Brno, República Checa; Universidad de Colonia); L. Labadie (Universidad de Colonia);, E. Bordier (Universidad de Colonia); A. Eckart (Universidad de Colonia; Instituto Max Planck de Radioastronomía, Bonn, Alemania); M. Melamed (Universidad de Colonia) y V. Karas (Instituto Astronómico, Academia Checa de Ciencias, Praga, República Checa).

English version #

First ever binary star found near our galaxy’s supermassive black hole #

“Black holes are not as destructive as we thought,” said Florian Peißker, a researcher at the University of Cologne, Germany, and lead author of the study published in Nature Communications. Binary stars, pairs of stars orbiting each other, are very common in the Universe, but they had never before been found near a supermassive black hole, where the intense gravity can make stellar systems unstable.

This new discovery shows that some binaries can briefly thrive, even under destructive conditions. D9, as the newly discovered binary star is called, was detected just in time: it is estimated to be only 2.7 million years old, and the strong gravitational force of the nearby black hole will probably cause it to merge into a single star within just one million years, a very narrow timespan for such a young system.

“This provides only a brief window on cosmic timescales to observe such a binary system — and we succeeded!” explained co-author Emma Bordier, a researcher also at the University of Cologne and a former student at ESO.

For many years, scientists also thought that the extreme environment near a supermassive black hole prevented new stars from forming there. Several young stars found in close proximity to Sagittarius A* have disproved this assumption. The discovery of the young binary star now shows that even stellar pairs have the potential to form in these harsh conditions. “The D9 system shows clear signs of the presence of gas and dust around the stars, which suggests that it could be a very young stellar system that must have formed in the vicinity of the supermassive black hole,” explained co-author Michal Zajaček, a researcher at Masaryk University, Czechia, and the University of Cologne.

The newly discovered binary was found in a dense cluster of stars and other objects orbiting Sagittarius A, called the S cluster. Most enigmatic in this cluster are the G objects, which behave like stars but look like clouds of gas and dust*.

It was during their observations of these mysterious objects that the team found a surprising pattern in D9. _The data obtained with the VLT’s ERIS instrument, combined with archival data from the SINFONI instrument, revealed recurring variations in the velocity of the star, indicating D9 was actually two stars orbiting each other. “I thought that my analysis was wrong,” Peißker said, “but the spectroscopic pattern covered about 15 years, and it was clear this detection is indeed the first binary observed in the S cluster.”

We found something odd Two stars have been found orbiting each other in the vicinity of Sgr A*, the supermassive black hole at the centre of the Milky Way. A young binary star system forming and surviving in this extreme gravity means that black holes are not as destructive as we thought. This video summarises the discovery. Credit: ESO. Directed by: Angelos Tsaousis and Martin Wallner. Editing: Angelos Tsaousis. Web and technical support: Gurvan Bazin and Raquel Yumi Shida. Written by: Hanna Huysegoms. Music: Stellardrone – Ethereal. Footage and photos: ESO / Luis Calçada, Cristoph Malin (christophmalin.com), Martin Kornmesser, Florian Peißker et al., Nick Risinger (skysurvey.org), Schoedel, DSS, VISTA, EHT Collaboration, VVV Survey/D. Minniti Nogueras-Lara et al. Scientific consultant: Paola Amico, Mariya Lyubenova.

The results shed new light on what the mysterious G objects could be. The team proposes that they might actually be a combination of binary stars that have not yet merged and the leftover material from already merged stars.

Two stars dancing The animation shows how the two stars of the D9 star system orbit each other, enveloped in a cloud of gas and dust. The blue line indicates the orbit of the binary system around Sagittarius A*, the supermassive black hole at the centre of the Milky Way. D9 is the first ever binary star found near a supermassive black hole. Its formation and survival in this extreme environment means that black holes are not as destructive as we thought. Credit: ESO/M. Kornmesser

The precise nature of many of the objects orbiting Sagittarius A, as well as how they could have formed so close to the supermassive black hole, remain a mystery*. _But soon, the GRAVITY+ upgrade to the VLT Interferometer and the METIS instrument on ESO’s Extremely Large Telescope (ELT), under construction in Chile, could change this. Both facilities will allow the team to carry out even more detailed observations of the Galactic centre, revealing the nature of known objects and undoubtedly uncovering more binary stars and young systems. “Our discovery lets us speculate about the presence of planets, since these are often formed around young stars. It seems plausible that the detection of planets in the Galactic centre is just a matter of time,” concluded Peißker.

Closing up to the unexpected D9 binary system. The animation shows D9, the first ever star pair discovered near Sagittarius A*, the supermassive black hole at the centre of the Milky Way. We zoom in and out on the black hole and the single stars orbiting it, to then get close to D9, the first ever binary star system found in its vicinity. The video, which was made by an artist at the Brno Observatory and Planetarium, shows how the star system orbits the black hole. It also reveals the dusty gas cloud in which the star pair is enveloped, which suggests it is a young star system. The formation and survival of a binary star system in this extreme environment means that black holes are not as destructive as we thought. This animation was made possible thanks to a Czech Science Foundation Junior Star grant (GM24-10599M). Credit: P. Karas (Brno Observatory and Planetarium), RSA Cosmos Sky Explorer. Acknowledgements: M. Zajaček, F. Peißker and Czech Science Foundation

- The paper “A binary system in the S cluster close to the supermassive black hole Sagittarius A”* was published in Nature Communications (doi: 10.1038/s41467-024-54748-3). Authors: F. Peißker (Institute of Physics I, University of Cologne, Germany [University of Cologne]), M. Zajaček (Department of Theoretical Physics and Astrophysics, Masaryk University, Brno, Czechia; University of Cologne), L. Labadie (University of Cologne), E. Bordier (University of Cologne), A. Eckart (University of Cologne; Max Planck Institute for Radio Astronomy, Bonn, Germany), M. Melamed (University of Cologne), and V. Karas (Astronomical Institute, Czech Academy of Sciences, Prague, Czechia).

Notas al pie / Footnotes #

-

Un objeto G en astronomía se refiere a un tipo específico de cuerpo celeste que ha sido objeto de estudio en el contexto de la formación y evolución de estrellas. Se ha propuesto que los objetos G son el resultado de fusiones estelares, en donde dos estrellas que orbitan entre sí se combinan, crean un nuevo tipo de objeto. Respecto a su origen, se cree que los objetos G pueden haber sido en el pasado estrellas binarias, es decir, sistemas de dos estrellas que orbitan mutuamente. Los investigadores han estudiado estos objetos y su relación con el centro de nuestra galaxia, sugiriendo que podrían estar relacionados con procesos de fusión estelar. En cuanto a sus características, si bien se desconocen los detalles sobre su composición y comportamiento, se considera que estos objetos son importantes para entender la dinámica y evolución de las estrellas en nuestra galaxia, la Vía Láctea. ↩︎