Maravillas de las islas subterráneas en el submundo terrestre

Table of Contents

Ocultas en lo profundo del manto terrestre se encuentran dos enormes “islas” del tamaño de continentes. Un nuevo estudio de la Universidad de Utrecht reveló que estas regiones no sólo son más calientes que el frío cementerio de placas tectónicas que las rodea, sino también más antiguas: al menos 500 millones de años, e incluso aún más. Estas observaciones contradicen la idea de un manto terrestre homogéneo que se mezcla rápidamente, una teoría cada vez más cuestionada. “Hay menos flujo en el manto de la Tierra de lo que comúnmente se piensa”. Esta investigación fue publicada en Nature.

Un terremoto de gran magnitud genera ondas que hacen vibrar toda la Tierra, haciéndola resonar como una campana y emitir diversos tonos, similares a los de un instrumento musical. Los sismólogos que estudian el interior profundo de la Tierra investigan hasta qué punto estos tonos están “desafinados”, ya que estas grandes vibraciones terrestres podrían sonar desafinadas o más débiles al atravesar anomalías estructurales. De este modo, los sismólogos generan imágenes del interior de nuestro planeta, de la misma manera que un médico utiliza rayos X para observar el interior del cuerpo humano. A finales del siglo pasado, un análisis de estas vibraciones reveló la existencia de dos “supercontinentes” subterráneos: uno ubicado debajo de África y otro debajo del océano Pacífico, ambos ocultos a más de dos mil kilómetros bajo la superficie terrestre. “Nadie sabía qué eran, si eran solo un fenómeno temporal, o si habían permanecido ahí desde hace millones, o quizás incluso miles de millones de años”, afirmó Arwen Deuss, sismóloga y catedrática en Estructura y Composición del Interior Profundo de la Tierra de la Universidad de Utrecht, Países Bajos. “Estas dos grandes islas están rodeadas por un cementerio de placas tectónicas que han sido transportadas hasta allí por un proceso llamado ‘subducción’, en el que una placa tectónica se sumerge bajo otra y se hunde desde la superficie terrestre hasta una profundidad de casi tres mil kilómetros”.

Ondas lentas y la clave de la amortiguación #

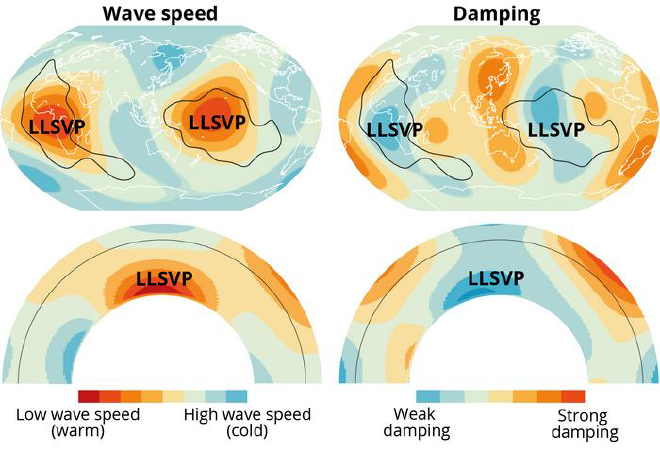

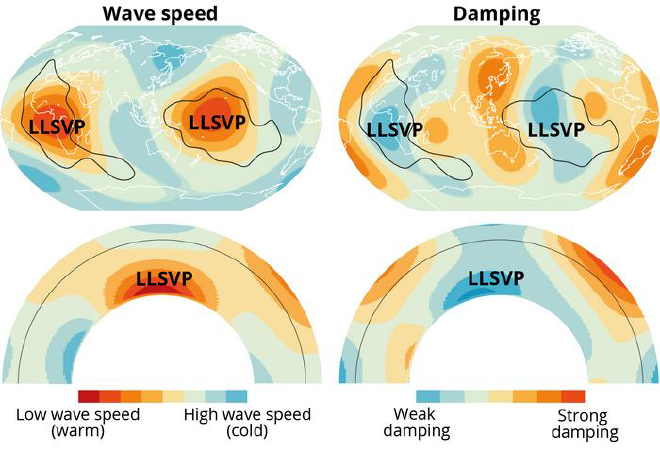

“Sabemos desde hace años que estas islas se encuentran en el límite entre el núcleo y el manto de la Tierra, y hemos observado que las ondas sísmicas se desaceleran al atravesarlas”. Por esta razón, los geocientíficos llaman a estas regiones las grandes provincias de baja velocidad sísmica (o LLSVP, por sus siglas en inglés). “Las ondas se desaceleran porque las LLSVP son más calientes, de la misma manera que corremos más lento cuando hace calor que cuando hace frío”. Deuss y su colega Sujania Talavera-Soza querían averiguar si podían descubrir algo más sobre estas regiones. “Añadimos un nuevo parámetro, la ‘amortiguación’ de las ondas sísmicas, que es la cantidad de energía que pierden las ondas al propagarse a través de la Tierra. Para ello, no solo investigamos qué tan desafinados están los tonos de la Tierra, sino que también estudiamos su volumen sonoro”, dijo Deuss. Talavera-Soza añadió que “contrario a nuestras expectativas, encontramos muy poca amortiguación en las LLSVP, lo cual produce tonos altos en esta región. Sin embargo, sí encontramos una gran amortiguación en el frío cementerio de placas tectónicas, donde se generan tonos muy bajos, contrario a lo que ocurre en el manto superior, donde encontramos exactamente lo que esperábamos: altas temperaturas y ondas amortiguadas. Igual que cuando hace calor y sales a correr, no sólo vas más despacio, sino que te cansas más que cuando hace frío”.

El tamaño de grano revela la antigüedad #

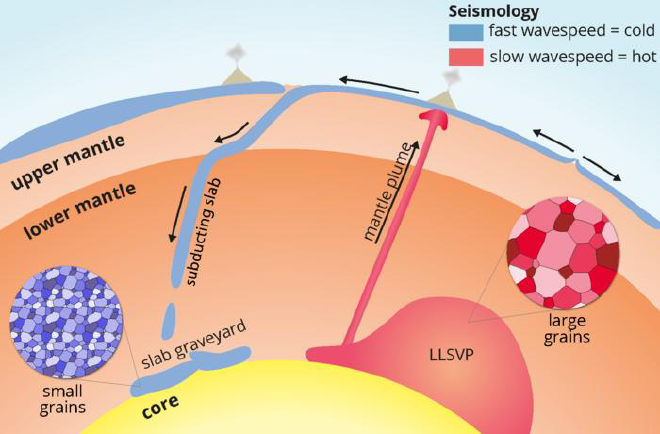

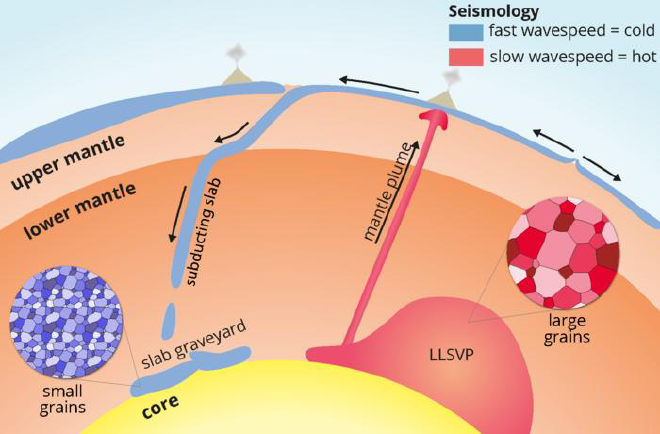

Su colega Laura Cobden, especialista en los minerales de las profundidades terrestres, sugirió estudiar el tamaño de grano de las LLSVP. Según su colega estadounidense Ulrich Faul, la temperatura por sí sola no puede explicar la ausencia de alta amortiguación en las LLSVP. “El tamaño de grano es un factor mucho más importante. Las placas tectónicas en subducción, que descienden hasta el llamado cementerio de placas, están compuestas por granos pequeños, ya que se recristalizan durante su viaje hacia las profundidades de la Tierra. Un tamaño de grano pequeño implica un mayor número de granos y, en consecuencia, un mayor número de límites entre ellos. Debido al gran número de fronteras entre los granos en el cementerio de placas, se produce una mayor amortiguación, ya que las ondas pierden energía al atravesar cada una de estas fronteras. El hecho de que las LLSVP muestren muy poca amortiguación indica que deben estar formadas por granos mucho más grandes” concluyó Deuss.

Antigüedad y estabilidad: implicaciones para el manto terrestre #

Estos granos minerales no surgen de la noche a la mañana, lo que sólo puede significar una cosa: las LLSVP son significativamente más antiguas que los cementerios de placas que las rodean. Además, las LLSVP, compuestas por bloques de construcción mucho más grandes, son mucho más rígidas. Por lo tanto, no participan en la convección del manto (el flujo de materia que ocurre en el interior del manto terrestre). De este modo, contrariamente a lo que nos enseñan los libros de geografía, el manto no puede estar completamente mezclado. Talavera-Soza aclaró que después de todo, las LLSVP deben haber resistido a la convección del manto de alguna manera."

El manto como motor de la Tierra #

Comprender cómo funciona el manto terrestre es fundamental para entender la evolución de nuestro planeta. “Y también para entender otros fenómenos que ocurren en la superficie terrestre, como el vulcanismo y la formación de montañas”, añadió Deuss. “El manto terrestre es el motor de todos estos fenómenos. Tomemos como ejemplo los penachos térmicos del manto: grandes columnas de material caliente que ascienden desde las profundidades de la Tierra, como en una lámpara de lava.” Al llegar a la superficie, generan vulcanismo, como el que se observa en Hawái. “Y creemos que estos penachos térmicos tienen su origen en los márgenes de las LLSVP”, detalló.

El papel de los terremotos de gran magnitud #

En este tipo de investigación, los sismólogos utilizan las vibraciones generadas por terremotos de gran magnitud, preferentemente aquellos que ocurren a grandes profundidades, como el terremoto de Bolivia de 1994. “Este terremoto no fue muy difundido en los periódicos, porque ocurrió a gran profundidad, a 650 km bajo la superficie y, afortunadamente, no causó daños ni víctimas”, explicó Deuss. Todas las vibraciones terrestres, o tonos, están descritas matemáticamente, de manera que no sólo podemos “leer” fácilmente la amortiguación (es decir, la intensidad de la oscilación), sino que también podemos atribuirla a una estructura en específico y distinguirla de la velocidad de la onda (es decir, cuán desafinada está). “Este hecho resulta impresionante dado que la amortiguación de la señal constituye sólo una décima parte del total de información que podemos extraer de estas vibraciones”. Para este tipo de investigación, no es necesario esperar a que ocurra otro terremoto. Los datos de terremotos pasados son extremadamente valiosos. “Podemos utilizar los registros desde 1975, ya que a partir de ese año los sismómetros alcanzaron un nivel de calidad alto que nos proporcionan datos lo suficientemente precisos para nuestra investigación.”, detalló.

- El paper Global 3D model of mantle attenuation using seismic normal modes, basado en un estudio experimental, fue publicado en Nature. Autores: Sujania Talavera-Soza, Laura Cobden, Ulrich H. Faul & Arwen Deuss

English version #

Subterranean ‘islands’: strongholds in a potentially less turbulent world #

Earth’s mantle reveals hidden treasures

Deeply hidden in Earth’s mantle there are two huge ‘islands’ with the size of a continent. New research from Utrecht University shows that these regions are not only hotter than the surrounding graveyard of cold sunken tectonic plates, but also that they must be ancient: at least half a billion years old, perhaps even older. These observations contradict the idea of a well-mixed and fast flowing Earth’s mantle, a theory that is becoming more and more questioned. “There is less flow in Earth’s mantle than is commonly thought.” This research was published in Nature.

Large earthquakes make the whole Earth ring like a bell with different tones, just like a musical instrument. Seismologists study Earth’s deep interior by investigating how much these tones are ‘out of tune’, because whole Earth oscillations will sound out of tune or less loud when they encounter anomalies. This way seismologists will be able to make images of the interior of our planet, just like a hospital doctor can ‘see’ through your body with X-rays. At the end of the last century, an analysis of these oscillations showed the existence of two subsurface ‘super-continents’: one under Africa and the other one under the Pacific Ocean, both hidden more than two thousand kilometers below the Earth’s surface. “Nobody knew what they are, and whether they are only a temporary phenomenon, or if they have been sitting there for millions or perhaps even billions of years,” says Arwen Deuss, seismologist and professor of Structure and Composition of Earth’s deep interior at Utrecht University in the Netherlands. “These two large islands are surrounded by a graveyard of tectonic plates which have been transported there by a process called ‘subduction’, where one tectonic plate dives below another plate and sinks all the way from the Earth’s surface down to a depth of almost three thousand kilometres.”

Slow waves #

“We have known for years that these islands are located at the boundary between the Earth’s core and mantle. And we see that seismic waves slow down there.” Earth scientists therefore call these regions ‘ Large Low Seismic Velocity Provinces’ or LLSVPs. “The waves slow down because the LLSVPs are hot, just like you can’t run as fast in hot weather as you can when it’s colder.” Deuss and her colleague Sujania Talavera-Soza were keen to find out if they could discover more about these regions. “We added new information, the so-called ‘damping’ of seismic waves, which is the amount of energy that waves lose when they travel through the Earth. In order to do so, we did not only investigate how much the tones where out of tune, we also studied their sound volume.” Talavera-Soza adds: “Against our expectations, we found little damping in the LLSVPs, which made the tones sound very loud there. But we did find a lot of damping in the cold slab graveyard, where the tones sounded very soft. Unlike the upper mantle, where we found exactly what we expected: it is hot, and the waves are damped. Just like when the weather is hot outside and you go for a run, you don’t only slow down but you also get more tired than when it is cold outside.”

Grain size #

Their colleague Laura Cobden, who specializes in the minerals that we find deep in the Earth, suggested to study the grain size of the LLSVPs. According to their American colleague Ulrich Faul, temperature alone cannot explain the absence of high damping in the LLSVPs. Deuss explained that ”grain size is much more important. Subducting tectonic plates that end up in the slab graveyard consist of small grains because they recrystallize on their journey deep into the Earth. A small grain size means a larger number of grains and therefore also a larger number of boundaries between the grains. Due to the large number of grain boundaries between the grains in the slab graveyard, we find more damping, because waves loose energy at each boundary they cross. The fact that the LLSVPs show very little damping, means that they must consist of much larger grains.”

Ancient #

Those mineral grains do not grow overnight, which can only mean one thing: LLSVPs are lots and lots older than the surrounding slab graveyards. Even more so: the LLSVPs, with their much larger building blocks, are very rigid. Therefore, they do not take part in mantle convection (the flow in the Earth’s mantle). Thus, contrary to what the geography books teach us, the mantle cannot be well-mixed either. Talavera-Soza clarified: “After all, the LLSVPs must be able to survive mantle convection one way or another.”

Engine #

Knowledge of the Earth’s mantle is essential to understand the evolution of our planet. “And also to understand other phenomena at the Earth’s surface, such as vulcanism and mountain building,” added Deuss. “The Earth’s mantle is the engine that drives all these phenomena. Take, for example, mantle plumes, which are large bubbles of hot material that rise from the Earth’s deep interior as in a lava lamp.” Once they finally reach the surface, they cause vulcanism, like under Hawaii. “And we think that those mantle plumes originate at the edges of the LLSVPs.”

Large earthquakes #

In this type of research, seismologists make good use of oscillations caused by really large earthquakes, preferably quakes that take place at great depths, such as the great Bolivia earthquake of 1994. “It never made it into the newspapers, because it took place at a large depth of 650 km and luckily did not result in any damage or casualties at the Earth’s surface,” Deuss explained. The whole Earth oscillations, or tones, are mathematically described in such a way that we can easily ‘read’ the damping (i.e. how loud the oscillation is) due to a specific structure and separate it from the wave speed (i.e. how much out of tune it is). “Which is impressive, because the damping of the signal is only one-tenth of the total amount of information that we can unravel from these oscillations.” For this type of research, it is not necessary to wait until another earthquake occurs. The data from previous earthquakes is just as useful. “We can go back to 1975, because from that year onwards, seismometers became good enough to give us data of such high quality that they are useful for our research.”

- The paper Global 3D model of mantle attenuation using seismic normal modes, an observational study, was published in Nature. Authors: Sujania Talavera-Soza, Laura Cobden, Ulrich H. Faul & Arwen Deuss