Vientos supersónicos extremos medidos en un planeta fuera de nuestro Sistema Solar

Table of Contents

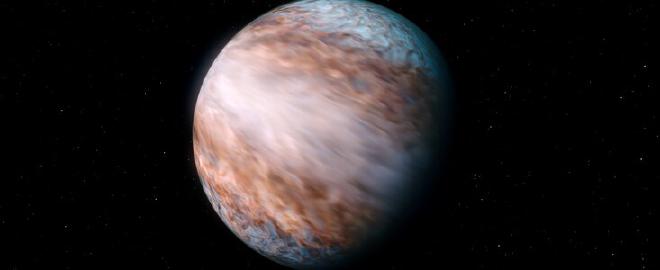

Tornados, ciclones y huracanes causan estragos en la Tierra, pero los científicos ahora han detectado vientos planetarios en una escala completamente diferente, muy fuera del Sistema Solar. Desde su descubrimiento en 2016, los astrónomos han estado investigando el clima en WASP-127b, un planeta gaseoso gigante ubicado a más de 500 años luz de la Tierra. El planeta es ligeramente más grande que Júpiter, pero tiene sólo una fracción de su masa, lo que lo hace ‘hinchado’. Ahora, un equipo internacional de astrónomos ha hecho un descubrimiento inesperado: vientos supersónicos azotan el planeta.

“Parte de la atmósfera de este planeta se acerca a nosotros a gran velocidad mientras que otra parte se aleja de nosotros a la misma velocidad”, afirmó Lisa Nortmann, científica de la Universidad de Göttingen, Alemania, y autora principal del estudio. “Esta señal nos muestra que hay un viento en chorro supersónico muy rápido alrededor del ecuador del planeta”.

A 9 km por segundo (cerca de 33.000 km/h), los vientos en chorro se mueven a casi seis veces la velocidad a la que gira el planeta.

Si bien el equipo no ha medido la velocidad de rotación del planeta directamente, esperan que WASP-127b esté bloqueado por mareas, lo que significa que el planeta tarda tanto en girar alrededor de su propio eje como en orbitar la estrella. Sabiendo qué tan grande es el planeta y cuánto tiempo tarda en orbitar su estrella, pueden inferir a qué velocidad está girando.

“Esto es algo que no habíamos visto antes”, expresó Nortmann. Se trata del viento más rápido jamás medido en una corriente en chorro que gira alrededor de un planeta. En comparación, el viento más rápido jamás medido en nuestro Sistema Solar se halló en Neptuno, moviéndose a ‘sólo’ 0,5 km por segundo (1800 km/h).

El equipo, cuya investigación se publicó hoy en Astronomy & Astrophysics, cartografió el clima y la composición de WASP-127b utilizando el instrumento CRIRES+ en el VLT de ESO. Midiendo cómo viaja la luz de la estrella anfitriona a través de la atmósfera superior del planeta, lograron rastrear su composición. Sus resultados confirman la presencia de moléculas de vapor de agua y monóxido de carbono en la atmósfera del planeta. Pero cuando el equipo rastreó la velocidad de este material en la atmósfera, observaron, para su sorpresa, un doble pico, lo que indica que un lado de la atmósfera se mueve hacia nosotros y el otro se aleja a gran velocidad. Los investigadores concluyen que los potentes vientos en chorro alrededor del ecuador explicarían este resultado inesperado.

Ampliando aún más su mapa meteorológico, el equipo también descubrió que los polos son más fríos que el resto del planeta. También hay una ligera diferencia de temperatura entre los lados matutino y vespertino de WASP-127b. “Esto demuestra que el planeta tiene patrones climáticos complejos al igual que la Tierra y otros planetas de nuestro propio Sistema”, añadió Fei Yan, coautor del estudio y profesor de la Universidad de Ciencia y Tecnología de China.

El campo de la investigación de exoplanetas avanza rápidamente. Hasta hace unos años, los astrónomos sólo podían medir la masa y el radio de los planetas fuera del Sistema Solar. Hoy en día, telescopios como el VLT de ESO ya permiten a los científicos mapear el clima en estos mundos distantes y analizar sus atmósferas. “Comprender la dinámica de estos exoplanetas nos ayuda a explorar mecanismos como la redistribución del calor y los procesos químicos, mejorando nuestra comprensión de la formación de planetas y potencialmente arrojando luz sobre los orígenes de nuestro propio Sistema Solar”, dijo David Cont de la Universidad Ludwig Maximilian de Munich, Alemania y coautor del artículo.

Curiosamente, en la actualidad, estudios como este sólo pueden realizarse desde observatorios terrestres, ya que los instrumentos que actualmente se encuentran en los telescopios espaciales no tienen la velocidad de precisión necesaria. El Telescopio Extremadamente Grande de ESO, que está en construcción cerca del VLT en Chile, y su instrumento ANDES permitirán a los investigadores profundizar aún más en los patrones climáticos en planetas lejanos. “Esto significa que probablemente podamos resolver detalles aún más finos de los patrones del viento y ampliar esta investigación a planetas rocosos más pequeños”, concluyó Nortmann.

-

Esta investigación fue presentada en el artículo “CRIRES+ transmission spectroscopy of WASP-127b. Detection of the resolved signatures of a supersonic equatorial jet and cool poles in a hot planet”, publicado hoy en Astronomy & Astrophysics (doi: 10.1051/0004-6361/202450438).

-

El equipo está compuesto por L. Nortmann (Instituto de Astrofísica y Geofísica, Universidad Georg-August, Göttingen, Alemania [IAG]), F. Lesjak (IAG), F. Yan (Departamento de Astronomía, Universidad de Ciencia y Tecnología de China, Hefei, China), D. Cont (Observatorio Universitario, Facultad de Física, Universidad Ludwig-Maximilians de Múnich, Alemania; Grupo de Orígenes de Excelencia, Garching, Alemania), pág. Czesla (Thüringer Landessternwarte Tautenburg, Alemania [TLS]), A. Lavail (Institut de Recherche en Astrophysique et Planétologie, Université de Toulouse, Francia), A. D. Rains (Departamento de Física y Astronomía, Universidad de Uppsala, Suecia [Universidad de Uppsala]), E. Nagel (IAG), L. Boldt-Christmas (Universidad de Uppsala), A. Hatzes (TLS), A. Reiners (IAG), N. Piskunov (Universidad de Uppsala), O. Kochukhov (Universidad de Uppsala), U.Heiter (Universidad de Uppsala), D. Shulyak (Instituto de Astrofísica de Andalucía, Glorieta de la Astronomía, España), M. Rengel ( Instituto Max Planck para la Investigación del Sistema Solar, Göttingen, Alemania) y U. Seemann (Observatorio Europeo Austral, Garching, Alemania).

English version #

Extreme supersonic winds measured on planet outside our Solar System #

Astronomers have discovered extremely powerful winds pummeling the equator of WASP-127b, a giant exoplanet. Reaching speeds up to 33 000 km/h, the winds make up the fastest jetstream of its kind ever measured on a planet. The discovery was made using the European Southern Observatory’s Very Large Telescope (ESO’s VLT) in Chile and provides unique insights into the weather patterns of a distant world.

Tornados, cyclones and hurricanes wreak havoc on Earth, but scientists have now detected planetary winds on an entirely different scale, far outside the Solar System. Ever since its discovery in 2016, astronomers have been investigating the weather on WASP-127b, a giant gas planet located over 500 light-years from Earth. The planet is slightly larger than Jupiter, but has only a fraction of its mass, making it ‘puffy’. An international team of astronomers have now made an unexpected discovery: supersonic winds are raging on the planet.

“Part of the atmosphere of this planet is moving towards us at a high velocity while another part is moving away from us at the same speed,” says Lisa Nortmann, a scientist at the University of Göttingen, Germany, and lead author of the study. “This signal shows us that there is a very fast, supersonic, jet wind around the planet’s equator.”

At 9 km per second (which is close to a whopping 33 000 km/h), the jet winds move at nearly six times the speed at which the planet rotates.

While the team hasn’t measured the rotation speed of the planet directly, they expect WASP-127b to be tidally locked, meaning the planet takes as long to rotate around its own axis as it does to orbit the star. Knowing how big the planet is and how long it takes to orbit its star, they can infer how fast it’s rotating.

“This is something we haven’t seen before,” explains Nortmann. It is the fastest wind ever measured in a jetstream that goes around a planet. In comparison, the fastest wind ever measured in the Solar System was found on Neptune, moving at ‘only’ 0.5 km per second (1800 km/h).

The team, whose research was published today in Astronomy & Astrophysics, mapped the weather and make-up of WASP-127b using the CRIRES+ instrument on ESO’s VLT. By measuring how the light of the host star travels through the planet’s upper atmosphere, they managed to trace its composition. Their results confirm the presence of water vapour and carbon monoxide molecules in the planet’s atmosphere. But when the team tracked the speed of this material in the atmosphere, they observed — much to their surprise — a double peak, indicating that one side of the atmosphere is moving towards us and the other away from us at high speed. The researchers conclude that powerful jetstream winds around the equator would explain this unexpected result.

Further building up their weather map, the team also found that the poles are cooler than the rest of the planet. There is also a slight temperature difference between the morning and evening sides of WASP-127b. “This shows that the planet has complex weather patterns just like Earth and other planets of our own System,” added Fei Yan, a co-author of the study and a professor at the University of Science and Technology of China.

The field of exoplanet research is rapidly advancing. Up until a few years ago, astronomers could measure only the mass and the radius of planets outside the Solar System. Today, telescopes like ESO’s VLT already allow scientists to map the weather on these distant worlds and analyse their atmospheres. “Understanding the dynamics of these exoplanets helps us explore mechanisms such as heat redistribution and chemical processes, improving our understanding of planet formation and potentially shedding light on the origins of our own Solar System,” said David Cont from the Ludwig Maximilian University of Munich, Germany, and a co-author of the paper.

Interestingly, at present, studies like this can only be done by ground-based observatories, as the instruments currently on space telescopes do not have the necessary velocity precision. ESO’s Extremely Large Telescope — which is under construction close to the VLT in Chile — and its ANDES instrument will allow researchers to delve even deeper into the weather patterns on far-away planets. “This means that we can likely resolve even finer details of the wind patterns and expand this research to smaller, rocky planets,” Nortmann concluded.

- This research was presented in the paper, “CRIRES+ transmission spectroscopy of WASP-127b. Detection of the resolved signatures of a supersonic equatorial jet and cool poles in a hot planet”, published today in Astronomy & Astrophysics (doi: 10.1051/0004-6361/202450438).

The team is composed of L. Nortmann (Institut für Astrophysik und Geophysik, Georg-August-Universität, Göttingen, Germany [IAG]), F. Lesjak (IAG), F. Yan (Department of Astronomy, University of Science and Technology of China, Hefei, China), D. Cont (Universitäts-Sternwarte, Fakultät für Physik, Ludwig-Maximilians-Universität München, Germany; Exzellenzcluster Origins, Garching, Germany), S. Czesla (Thüringer Landessternwarte Tautenburg, Germany [TLS]), A. Lavail (Institut de Recherche en Astrophysique et Planétologie, Université de Toulouse, France), A. D. Rains (Department of Physics and Astronomy, Uppsala University, Sweden [Uppsala University]), E. Nagel (IAG), L. Boldt-Christmas (Uppsala University), A. Hatzes (TLS), A. Reiners (IAG), N. Piskunov (Uppsala University), O. Kochukhov (Uppsala University), U.Heiter (Uppsala University), D. Shulyak (Instituto de Astrofísica de Andalucía, Glorieta de la Astronomía, Spain), M. Rengel (Max-Planck-Institut für Sonnensystemforschung, Göttingen, Germany), and U. Seemann (European Southern Observatory, Garching, Germany).